Issue 9 (Summer 2019), pp. 31-56

DOI: 10.6667/interface.9.2019.85

Genichi Ikuma

Hokkaido University

This paper discusses human-object relationships in Moscow Conceptualism, a central circle of Soviet unofficial art in the 1970-80s. The ideal image of humans and objects in Conceptualist works has been studied. For example, the American art historian Matthew Jesse Jackson reads the New Man in terms of the relationship between human beings and objects in unofficial art. Meanwhile, Ekaterina Degot interprets the interrelation between humanity and objects in Conceptualism in terms of the interrelation between the self and others. Yet, previous studies did not particularly focus on objects and subjectivity in Conceptualism. There is a strong possibility that Soviet objects influenced the works of Conceptualists. These objects would be keywords in Moscow Conceptualism studies. Thus, I would like to make an assumption to understand the Conceptualist view: Did they try not to rule the outer environment but to analyze the objects surrounding them instead? In other words, this paper is concerned with demonstrating how Conceptualists updated the interface between themselves and surrounding objects. I will investigate the Conceptualist attitude towards objects, to offer a revised understanding of Conceptualists as artists reflecting on their subjectivity via objects. Trends of unofficial art began to change in the 70s as Conceptualism was formed: artists were interested in new forms such as “actions” and “installations.” Kabakov, an originator of Conceptualism, began his career in painting and illustrations for children’s books, while younger generations were engaged in genre-straddling activity from the beginning. Given such stylistic diversity, this study covered different types of artists to gain better insight into objects in Conceptualism. In addition, since this school was not a monolithic organization, looking at other artists of the same age is useful. Thus, this paper first discusses works by Vladimir Yankilevsky who was not exactly a conceptualist. His contemporary Ilya Kabakov’s works are also studied to understand objects in Conceptualism. Lastly, texts and performances by younger Conceptualists Pepperstein and Monastyrski are discussed in detail.

Keywords: Moscow conceptualism, performance art, human object relationships

The public image of unofficial Soviet art is that of a resistance movement against the Soviet ideology. Artists such as Komar and Melamid who play with ideology have impressive attitudes. Unlike them, artists of Moscow Conceptualism (hereafter, Conceptualism) took a slightly different approach. Of course, they were sometimes involved with the problem of ideology, but they preferred to reflect on the fact that they are surrounded by an ideological environment rather than improving it. While Russian Avant-garde and Socialist Realism tried to rewrite a world view, Sots Art (Soviet version of Pop Art) appropriated its image. In contrast, Conceptualists were no longer attracted to such an active approach. Instead, they took note of how Soviet subjects are surrounded by ideological objects.

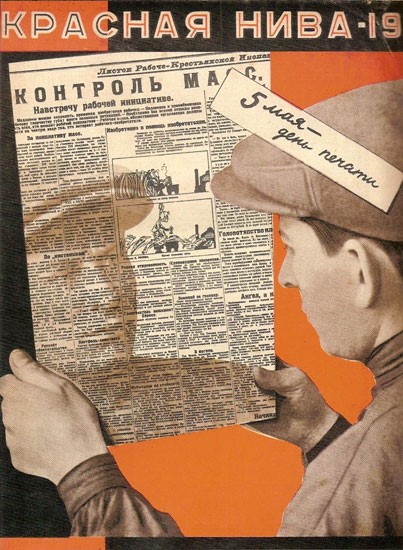

The most well-known among Soviet-style subjectivities would be the concept of the New Man. The American art historian Matthew Jesse Jackson (2010) reads the New Man in terms of the relationship between human beings and objects in unofficial art (p. 151). Meanwhile, Ekaterina Degot (2012) interprets the interrelation between humanity and objects in Conceptualism in terms of the interrelation between the self and others. She has written about Andrei Monastyrski (1949-), a leader of the Collective Actions group, and his works known as “action objects.” According to Degot, the artistic relationship here recalls constructivism. She notes that in constructivism, objects function as “comrade-things.” An example is Stenberg brothers’ (1930) Mirror of Soviet Community (Fig. 1). Degot notes that “in this object—a newspaper—he sees his mirror reflection, his own true image” (2012, pp. 30-31). However, as I will describe later, in addition to the projection of an ideal figure like the New Man, we can also find another kind of relationship. In other words, objects may not fully function as mirrors in Conceptualist works. This question about the status of objects in Conceptualism forms the basis for the present study.

Figure 1. Stenberg brothers, Mirror of Soviet Community (1930). (from Degot, 2011)

Keti Chukhrov (2012) also points out that the Conceptualists dealt with an already conceptualized world. She mentions Soviet objects like pliers that exist only for the specific function of bending something and asserts that Soviet objects are inseparably linked with their ideal usage, which she describes as “eidetic” (Chukhrov, 2012, p. 84). There is a strong possibility that these objects influenced the works of Conceptualists. These Soviet objects would be keywords in Moscow Conceptualism studies. Thus, I would like to make an assumption to understand the Conceptualist view: Did they try not to rule the outer environment but to analyze the objects surrounding them instead? In other words, this paper is concerned with demonstrating how Conceptualists updated the interface between themselves and surrounding objects.

In this regard, we should ask, “How and in what forms do humans encounter things?” To answer this question, I would like to examine a range of relationships in artists’ expressions. In the next section, I will discuss Vladimir Yankilevsky, who relates to the older painters of the 1950s and 1960s. While he is not exactly a Conceptualist, his concerns are similar to theirs (and he belonged to the same circle of artists as Kabakov in the 1960s.) Next, in Section 3, I will investigate objects in Conceptualism by reviewing the notion of Kabakov’s “bad quality.” In Section 4, I will investigate an essay by Pavel Pepperstein, a central figure of the younger generation of Conceptualists. Finally, in Section 5, I will analyze the performances of Collective Actions to reveal their view of objects.

Khrushchev then offered what he regarded as examples of good artists and artworks. He mentioned Solzhenitsyn, Mikhail Sholokhov, the song “Rushnichok,” and trees painted by some artist, in which the little leaves were so alive. (Yankilevsky, 2003-a, p. 75)

“You have an angel and a devil inside of you. We like the angel but we’ll eradicate the devil”. (Yankilevsky, 2003-a, p. 75)

The above passages come from Yankilevsky’s recollections of a conversation between Khrushchev and the sculptor Ernst Neizvestny (1925-2016) at the Thirty Years of MOSKh exhibition held in 1962. This served to determine the course of unofficial art since Khrushchev severely criticized the tendency toward abstraction among painters. Ely Beliutin(1925-2012), who organized the exhibition, sent a letter to the authorities saying “they wanted to sing the praises of ‘the beauty of Russian womanhood’” (Yankilevsky, 2003, p. 75), although Beliutin himself was involved in abstract painting. Yankilevsky must have been surprised by Beliutin’s behavior, which could be viewed as a recantation. In a way, this duality of pursuing the avant-garde and ingratiating the authorities corresponds to the “angel” and “devil” within Neizvestny. On the angel side, there were the “trees painted by some artist, in which the little leaves were so alive,” and “the beauty of Russian womanhood.” These represent beauty, health, aliveness, and the conception of an ideal life. On the other hand, Khrushchev saw abstraction as the “devil” for him and the USSR. Hearing this conversation, Yankilevsky must have sensed the collision or dichotomy of the two principles. After that, the devil Khrushchev failed to eradicate must have searched for another relationship with the medium of art (i.e., “things”), retaining this structure of two contrary principles while moving deeper underground.

The art critic Ekaterina Degot (2002, p. 163) calls Yankilevsky’s work “explosive anthropology”. Though she does not fully clarify this statement, we can understand that his creation expresses “a mutation of human being and machine” (Degot, 2002, p. 163). What “explodes” in his works, therefore, is the human shape and the human itself. Most humans he describes are strange combinations of machine and monster. In Yankilevsky’s works, there is an image of the human body in which the human shape “explodes.” Here, the outline of the human body is not closed but has an open existence outside the body.

The passage below describes Yankilevsky’s aesthetic of two principles and bodily representation. His works do not reflect the lively ideal advocated by Khrushchev but question such an ideal, pointing to the barriers posed by Soviet life.

The theme of “male principles” is also the theme of the “portraits.” Several ideas such as “a prophet,” “the living and the dead,” “I and he,” and “father and son” are connected in this theme.The theme “the living and the dead” is a theme of disagreement between “inside” and “outside.” It has always been impressive for me that a living man is “not equal” to himself in the sense that his life crosses over the outer border like radiation. It is an energy of the eyes, language, listening, and thinking. When this energy as radiation goes out —that is, when the human dies— the mask is equal to himself; in other words, the death remains. This collision between the facial outline —which “resembles” but is dead, like the mask— and the living energy is also a theme of my “portraits.” (Yankilevsky, 2003-b, p. 29)

This collision between two spheres is imprinted on the human body, and Yankilevsky’s work expresses this situation. Yankilevsky suggests that the human being does not correspond to itself. Here, movements “of the eyes, language, listening, and thinking” cause the person to be discordant with himself or herself. In this sense, we can understand Degot’s notion of “explosive anthropology” as a radiant movement of energy transfer between such spheres as “man and woman,” “life and death,” “inside and outside,” “self and other,” and “parents and children.” It is important to note that these binary components are represented and conceived through the human body. Based in the human body, living energy radiates from inside to outside. The passage below shows that for Yankilevsky, the functions of the human body are directly connected with beauty of life:

What is beauty? In my opinion, it is life. Why does a dead body cause unconscious fear? Why is it that the more natural a mannequin is made, the more unnatural it looks, and the more it resembles the dead? Probably because life is radiation and energy transfer. It is necessary that a nostril inhales air, eyes see, an ear receives a signal of sound, a brain digests information and makes decisions, and a controversial sense called telepathy is provided in order to keep human beings living. (Yankilevsky, 2003-b, p. 102)

We can say that “telepathy” for Yankilevsky also represents the ability of humans to connect inside and outside. This ability is necessary to “determine a position for himself, keep balance, and so that human legs go in the necessary direction” (Yankilevsky, 2003-b, p. 102). In other words, life for Yankilevsky is an adjustment between inside and outside the body and locating oneself in the relationship between inside and outside. A mannequin is a mask that only corresponds to itself and looks dead because it lacks radiation and transfer through difference. Importantly, telepathy provides the orientation for walking and is not expressed as something fixed. Further, this transfer is not transparent but opaque, and it requires a groping process.

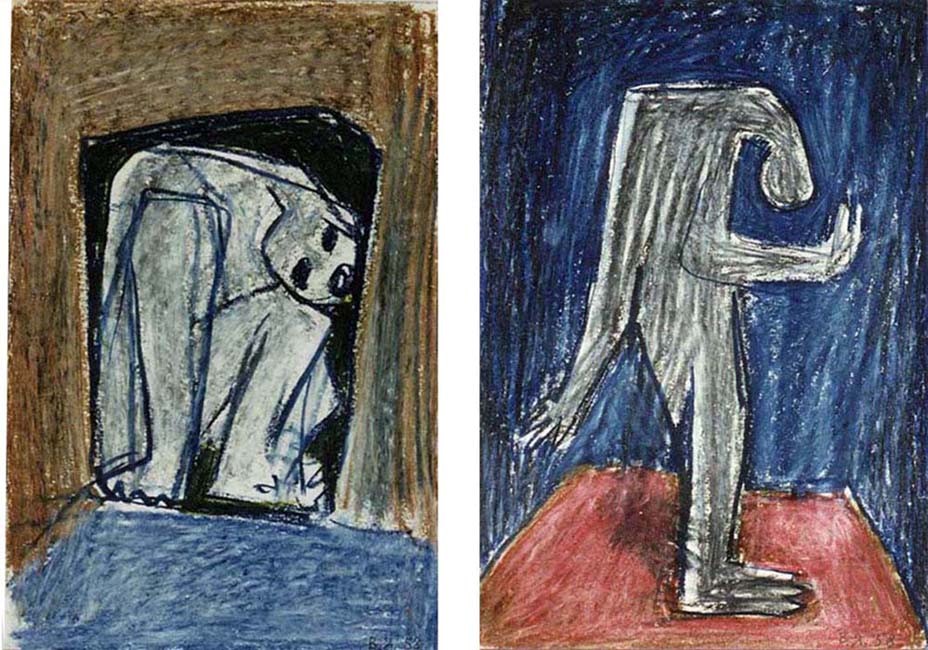

Figure 2. Yankilevsky, Man in the Box (1958). (from Yankilevsky, n.d.-a)

A wall and a box appear as things that disturb such a linking with the outside and solidify a body, as with the dead. For example, there are two figures in Yankilevsky’s Man in the Box (Fig. 2, 1958): a man doubled over in a box is shown on the left while on the right a figure stands freely, arms and neck bent mysteriously. The man in the box bears some resemblance to the mannequin Yankilevsky refers to, and the other man is rather similar to the monster. This contrast shows that a human lacking a connection to the outside looks like a mannequin—that is, a dead thing. This shows that since 1958, Yankilevsky has embraced this idea that humanity dwells in the intersection between inside and outside. Since then, Yankilevsky has further developed this idea by making a series of works called People in Boxes (Fig. 3, 1990), in which people strike strange poses inside boxes. Their existence is depicted as covered or blocked by things, especially walls. The presence of two black garbage bags is suggestive as well.

Figure 3. Yankilevsky, People in Boxes (1990). (from Yankilevsky, n-d.-b)

Does Moscow conceptualism always evoke the kind of alienation we find in Yankilevsky’s works? In a poem by Yankilevsky (2003-b, p. 105), a character becomes a picture: “you become a picture / and crucify yourself / so that someone could revive / you once again.” Thus, becoming a picture internalizes a hope for revival by the other person in the poem. In becoming a picture (i.e., a passive existence), the character in the poem wants to entrust his revival to someone else’s subjectivity. Does this type of conceit share common ground with conceptualist aesthetics? In the next section, I will describe the nature of subjectivity in relation to things in Kabakov’s thinking.

The Russian art historian Ekaterina Bobrinskaya (2013, p. 333) finds a genealogy of “bad art” in Soviet unofficial art, referring to the idea of Kabakov’s “bad quality.” It is said that at the beginning of his artistic activities, Kabakov realized that surrounding things were “bad” and that his works were “bad” as well. Here, “bad” does not refer to aesthetic quality but to the unstable borders or outlines of things. His thinking about “bad quality” begins with sculpture. According to Kabakov, a sculpture is a reckless trial aiming to slip away from whole material and obtain a separate form. In this correlation between a cohesive whole and the individual form, he sees “antagonism between two principles, namely, subjective living things and unaware dead souls” (Kabakov, 2008, p. 54). He calls his works “bad” because they contain the theme of being absorbed into a cohesive whole and escaping from it. In his works, this “bad quality” is closely associated with narrative, which creates meaning:

Now this is what I was feeling when I started to create objects-paintings. Finally, they had to maintain this double nature. On the one hand, “things” must have spoken something, suggested some connection, looked like something (paintings, plots, anecdotes, namely, meanings). On the other hand, they had to disappear slowly into something integral and faceless, or the nothing, with other objects in the room in which they exist—that is, a wall, chairs, an overcoat, a desk, and so on. (Kabakov, 2008, p. 55)

The idea that “antagonism between two principles, namely, subjective living things and unaware dead souls,” hides in the thing itself reminds us of the collision of two principles in Yankilevsky’s aesthetic. However, Kabakov’s interests are more social. According to Bobrinskaya (2013, p. 336), his themes refer to the “mechanism of the interpretation of the ‘social sphere’ and its interaction with an individual, a private person.” It would appear, then, that Kabakov’s point about separation from a cohesive whole could apply to the position of unofficial art and the shape of the human being it describes. In this sense, “bad quality” and “bad art” are metaphors for the artists’ situation. In addition, it is worth noting that Kabakov’s ephemeral imagery of “bad quality” comprises a kind of speaking, which coincides with the artist’s situation and is deeply tied to Moscow conceptualism.

While there is not room here to fully trace Bobrinskaya’s argument regarding “bad art” in the genealogy of unofficial art, we should not overlook the theme of “garbage” in relation to conceptualism and the importance of the artist’s gesture in abstract expressionism. Regarding abstract paintings, Bobrinskaya (2013, p. 353) focuses on how artists handle the connection between inside and outside: just as Western pop art and neo-Dada emerged in opposition to the idea in abstract expressionism and informalism that the expression of the artist’s mentality could be directly connected with the social sphere, there is also a protest against the expression of the artist’s mentality in “bad art.” Moreover, just as the gesture of painting itself is more important than canvases and colors in abstract expressionism, Soviet expressive abstraction, according to Bobrinskaya (2013, pp. 355, 359), was an explosion of individuals and liberation from the traditional painting that was affected by social restrictions.

A skeptical attitude to such expressive art questions the artist’s image as a born genius or superman. Previous research supports this point. According to Jackson (2010, p. 25), Kabakov’s teacher by negative example was Anatoly Zverev (1931-1986), a painter with expressive tendencies who was a central figure in the first generation of unofficial art. Zverev’s natural gift for making all things he touched gold, and for accomplishing five-year plans in four years despite his uncultured nature, was difficult for Kabakov to accept. Moreover, this image of Zverev was similar to that of government officials such as Khrushchev and Brezhnev. In other words, Kabakov saw the signs of the “superhuman” qualities associated with Khrushchev and Brezhnev in the figure of the unofficial artist, who was generally thought of as the opposite of politicians. We can say that Kabakov tried to deny this type of lofty subjectivity, and it is suggestive that he mentioned an alchemical aspect of Zverev’s work. We can suppose that the expressive and transparent relationship between artist and canvas in Zverev’s work was strange to Kabakov. His concerns in this regard—Does everything the artist touches, every vestige of an artist’s breath, become approved as artwork? Is the canvas a transparent medium? —must have influenced his work.

Zverev appears again as the starting point for the “aesthetic of garbage,” which is the main feature of “bad art.” According to Bobrinskaya (2013, p. 344), he embodies the “aesthetic of garbage in the way that he paints with such garbage like a rag.” Here, artistic activity becomes an attraction while an artwork becomes a thing to which an artist only temporarily attaches value (Bobrinskaya, 2013, p. 344). It is by way of this temporariness that Bobrinskaya situates Zverev in the history of “bad art.” However, considering that Kabakov wanted to overcome his style, Zverev’s “magical” creation can be viewed as representative of what Kabakov wanted to update—namely, subjective authority.

The “aesthetic of garbage” is an essential theme for conceptualists like Kabakov and Monastyrski. Bobrinskaya (2013, pp. 379-380) takes Monastyrski’s “action objects” as examples. For his work Pile (1975), Monastyrski asked his friends to place useless things from their pockets on a desk and write their name, what they put, and the time on a list. Here, a pile of garbage-like things becomes a work of art. In the installation Box with Garbage (1986), Kabakov also connects garbage with words and interpretation by attaching tags with “verbal garbage” written on them—like abusive language or fragments of conversation—to garbage scattered in a box. Thus, Bobrinskaya (2013, p. 373) concludes that for Moscow conceptualism, garbage played a supplementary role to the viewer’s perception and documentation after it. This repeats the formulation that conceptualist work is completed only through discourse and documentation (Ioffe, 2013, p. 218).

However, we cannot afford to turn a blind eye to the fact that garbage is more than just a substitute for discourse. There were words written on the surface of garbage, namely, words expressed as garbage. If so, it could be argued that this gives words the shape of garbage. As is common with anthropologists, the anthropologist who documents the voices of the people is not always fully integrated with them. Kabakov might have been keeping his distance from the Soviet world by expressing words as garbage. Given his installation, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment (1985), in which the room full of Soviet objects like posters becomes a vaulting board towards the outer world, objects cannot be considered merely as substitutes for words (Groys, 2016, p. 3). Considering this, the next section will re-examine the relationship between objects and words in Pepperstein.

The main problem for Pepperstein is his relationship with things, and things are a cause of suffering (Pepperstein, 1998, p. 149). Though he does not give a clear reason, in his essay “Passo and Deactivation of Triumph (Пассо и детриумфация)” (1985), as well as the later commentary “Ice in the Snow (Лед в снегу)” (1996), we find that he was keenly aware of difficulties one may face with things. The problem of things appears to be an obsession with him.

At the beginning of “Passo and Deactivation of Triumph,” Pepperstein classifies the types of relationships between human beings and things (1998, pp. 81-83). According to him, these are of three types: the first is in which things hate people, the second is in which things love people, and the third is in which people obsess over things. A typical example of the third type is a collector, for whom things become an object of passion and are seen as an embodiment of passivity. It is therefore all the more important, Pepperstein says, to find out if we can recognize activity within things (1998, p. 84). In his opinion, discourse about it can be divided into two attitudes: a magical and scientific attitude to feel the radiant energy of things and to consider things as a certain type of body and a psychoanalytic attitude to see only the semiotic aspect of things.

Pepperstein’s discourse does not completely match these attitudes. In the middle of the text, he brings up the idea of combining characteristics previously expressed as “inner activity” or “the soul of objects” into a new term “passo,” which derives from passivity but means more than that. He described its elusive nature:

If “passo” represents speculative essence of objects, “passonarity (пассонарность)” is a field where passo reveals itself, namely, the place where our perception still can “jump into” while “passo” itself “jumps out” at the other end, allowing us to see it for only a moment, as a shaky, slippery, and indefinite shadow. (Pepperstein, 1998, p. 89.)

This movement can also be noted in another distinct term “Deactivation of Triumph (детриумфация).” Based on the theological way of understanding the world that natural world always gets rid of the tendency toward chaos and triumphs over its own uncertainty by shaping cosmos, Pepperstein defines this term as a deviation of things from fixed forms (1998, pp. 89-90). According to Pepperstein, environment controls the forms of things, but once the environmental balance is lost, the “passo” of things becomes free and things start transforming (1998, p. 90). Thus, these two new terms he introduced are closely connected to each other, and both relate to deviation, which reminds us of the “bad quality” of Soviet life that Kabakov described.

Then, what kind of relationship with such things does Pepperstein envision? After all, his main interest seems to be narrative: how we can talk about things. He says some people feel action of things and what matters is how we construct phrases (Pepperstein, 1998, p. 87). If this action of things means “passo,” why is it related to the manner of talking about things? The following text shows it is in the event of narration that the catalyst for a certain deviation or transformation is hidden.

A thing is an occurrence, but it obtains a special time in which it is realized. We use words when we talk about things. At that time, we potentially want to “talk by things,” namely, talk about things by things. That’s why we have a hunger for terms. In addition, we need, indeed, new terms because the introduction of a new term is always inconvenient and even illogical, but on the other hand, it has an enchanting power, just like a thing with inanimate loud laughter that falls from the sky. This laughter of things is infectious, even if it seems like a sound of knocking or bursting. The reason for the above is that it infects us not by laughter but by objecthood. We associate it with a skeletal frame within ourselves and other things that constitute us. (Pepperstein, 1998, p. 88)

The idea behind the thought that we talk by things, the objecthood of which infects us, may be a way of recognizing that words can be thought of as things. It is worthy of attention that Pepperstein especially emphasizes the introduction of new terms. This text ends with the final sentence that time given to such new terms as “passo” is very short, and that those terms are made to be born and die before your own eyes (Pepperstein, 1998, p. 92). As long as the life and death of terms cause the transformation of texts into things, it can be said that Pepperstein tries to demonstrate the behavior of “passo” in the very same text. This brief moment of shape formation reminds us of the “bad quality” that Kabakov argued. What is different here from Kabakov is that Pepperstein showed that a subject is also associated in some way with such action of deviation, that is, “passo,” describing the event of infection by objecthood. This is why narration has a connection with the behavior of things.

The term “thing-object” Pepperstein introduced in “Ice in the Snow” would be another example of that. First, he distinguishes things and objects. He provides representative examples of these two types: a treasure repository as a thing and a machine as an object. According to him (1998, p. 162), a machine is a conglomerate of objects that have an instrumental character and are designed as extensions of the human body. On the other hand, a treasure repository in this context is a thing that reflects the nonhuman world (such as the light from stars, the moon, the beauty of flowers). Pepperstein thinks this kind of dual principle, which is somewhat akin to Yankilevsky’s aesthetic, can potentially become integrated and give birth to a “thing-object” (1998, p. 162). Here, the human body is extended but also connected to the nonhuman world.

At this point, Pepperstein focuses more directly on the transformation of human beings, which was indirectly suggested in the description of “passo.” In other words, in his world of “thing-objects,” people can be affected by “passo” in relation to the passive activity of things, regardless of whether it is through words. Pepperstein’s suffering due to things may have its origins in their potential transformation. In my view, he alone cannot form this kind of understanding of things. Therefore, I would like to investigate whether transformation caused by things can also be observed in other conceptualists’ activities.

In this section, I will discuss the performances of the Collective Actions group. However, first, I would like to briefly touch on the early works of Monastyrski, by referring to Degot’s (2012) argument. She notes the elimination of inequality between the subject and object as one of the aims of communism (Degot, 2012, p. 30). This aim, she says, took the form of eliminating the inequality between the artist and the artwork, and there was a practice of regarding an artwork as a kind of unalienated subjectivity—that is, as a “comrade-thing” (Degot, 2012). As mentioned earlier, Degot regards Stenberg brothers’ Mirror of Soviet Community as a comrade-thing that reflects the truth of the citizen who reads the newspaper (Degot, 2012).

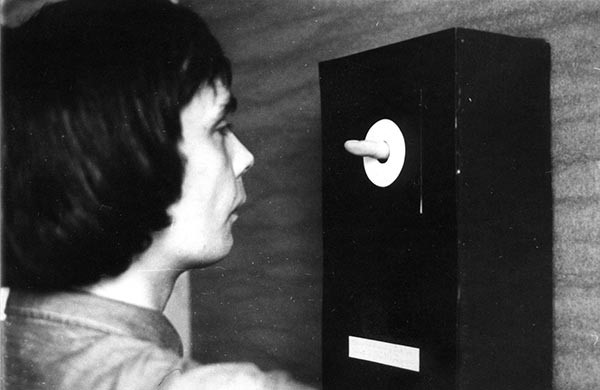

Figure 4. Finger by Monastyrski (1978). (from Monastyrski, n.d.-a)

Degot notes a similarity between Monastyrski’s action object Finger (Fig. 4) and the Stenberg brothers’ mirror (2012). The viewer of Finger (in this case, Monastyrski) puts his arm through the open bottom of a black box, pushes a finger through the white circular part of the box, and points at himself. The parallel between these two works is that both objects (the newspaper and the box) “gaze” at the viewer. Behind the relationship, there is a reflected image between humans and objects, which intends to turn objects into “comrades.” Degot sees a dual objectification of the subject in Finger: the artist is objectified both as an object that is being pointed at and as a fictional character (2012, p. 31). However, can we really say this work has the same composition as the Stenberg brothers’ mirror? Certainly, Monastyrski’s finger is objectified, but this is an asymmetric confrontation, different from the mirror image of the viewer in the newspaper (i.e., fingers have a different shape than faces). Therefore, we can suggest that the reflective similarity between the subject and the object is not emphasized but deconstructed using the black box. In other words, in this work, he disconnected his finger from his body. The following passages describe how Conceptualists have been disconnecting their own components and visualizing them as objects in the performances of Collective Actions, in a similar fashion.

Pepperstein is a member of the youngest generation of Moscow Conceptualists. Therefore, it is highly possible that his vision of infection by objects was developed based on observations of older conceptualists’ activities. In other words, Collective Actions may have influenced the development of Pepperstein’s thought. Through relationships with objects, Collective Actions seems to incorporate interfaces in interacting with the environment into components of their works. It is especially easy to notice the signature image of “being enclosed” in their performances. In what follows, I would like to analyze some actions of Collective Actions from this point of view.

THE TENT

Twelve stylized paintings of size 1x1 m each created by N. Alexeev were stitched into one cloth and put up like a tent in a forest not far from Moscow.

Moscow region, Savyolovskaya railway line, Depot station.2nd October, 1976. (Collective Actions Group, n.d.-a)

Despite its simplicity, one of their earliest actions, The Tent (1976), is important in terms of “enclosure.” In this action, a tent was created out of several clothes. Judging from the description of this action, even going inside the tent is not valued as essential content, setting aside the question of whether they really got inside or not. On the other hand, in For N. Panitkov (Three darkness) (1980), the tent’s interior attracted their attention. In this action, Panitkov, one of the main members of Collective Actions, sat down on a chair that was placed on a snow field. After that, a roof-like structure was constructed above his head, using some boards. Participants covered it with snow, and something like a snow hill was formed. Next, a blackout cloth was overlaid on this snow hill. Furthermore, they constructed a huge box made of clothes and papers around this snow hill while a radio was loudly playing. The title of the action refers to these three levels of enclosure. As in Yankilevsky’s work, there was man in the box in this action. Put simply, the most prominent part of this action was Panitkov’s being surrounded by darkness, severalfold.

7. Panitkov, having spent all the time in darkness inside his hill (the first darkness), stands up and rises the board.

8. After unsealing the hill, Panitkov is still surrounded by darkness (the second darkness of the cloth), as the hill is covered with cloth.

9. After dragging off the cloth, Panitkov still finds himself in darkness (the third darkness of the cloth). (Collective Actions Group, n.d.-b)

However, it is said that this darkness was not perfectly completed because of some trouble. This result is suggestive to a certain degree. At any rate, the theme of enclosure was just beginning to be clearly realized by them. The state of being enclosed gradually started to lead Conceptualists to more complex performances, beyond a mere expression of a sense of limitation. In a suggestive statement, Monastyrski connects the theme of enclosure to the dimension of documentation. By doing so, he shows that separation and enclosure are two sides of the same coin in this context.

In the actions before 10 Appearances and Playback, the events of the actions unfolded in a real exurban field (fields). After these two actions, these were already rather photographs of exurban fields, it was as if we separated ourselves from reality with a factographic membrane. We were clothed in dive suits of factography, in which we maneuvered in the subsequent actions. But even the places of these manipulations were similarly “packaged up” in a membrane of factography, changed somehow […].

(Monastyrski, n.d.-b)

In the action titled Playback (1981), participants observed a trace of a hammer on the wall of the artist’s apartment and heard sounds from tape recorders placed in front of and behind them. These recorders broadcasted not only the hammer blow sounds that were recorded before the action but also the sounds they made as they entered the room. They were surrounded by traces of themselves and simultaneously experienced two kinds of sounds, made by themselves and others.

In Music within and outside (1984), they created similar conditions, focusing their eyes on outer surroundings. First, organizers recorded sounds of a tram near a station while loudly playing musical instruments. The next day, Romashko, a member of Collective Actions, listened to these sounds on his headphones, standing at the same station where they had recorded. The following passage is cited from a text by Monastyrski who describes how they planned to make the sounds they called Music within and outside.

First of all, we thought of a French horn and oboe to be played by S.Letov (hereby we utilize the peculiar feature of “Letov’s tails” which was once planned for the action “Music of the Center”, but failed to put it into practice. Its nature is the following: Letov starts playing his instrument while a tram passes by and keeps sounding for a minute or two after it has already passed by the recorder. In “Music of the Centre” there was train instead of trams. Therefore, the recording is expected to contain a kind of acoustic traces, or tails – transport noises transform into musical tone). Secondly, we use a drum, N. Panitkov’s Buddhist ritual shell, a couple of bells, ringing of an alarm clock, a Chinese mouth harmonica and sometimes various vocal sonoristics.

But these things are secondary on the record, its primary content is the sound of trams passing by, while musical instruments are only embedded from time to time. Therefore, we were to record a soundtrack for “Music Within and Outside” – it seemed a fine name for this piece. A viewer’s visual attention could be focused on passing trams, anticipation of them, watching them run etc. At this point some peculiar coincidences could occur of recorded trams with real ones passing by.

(Collective Actions Group, n.d.-c)

To sum up, there was a coincidence between the three elements: previously recorded ambient sounds of the tram, the sounds of musical instruments that organizers played in tune with it, and the sounds of the tram on the day of action. This blurred the border between inside and outside. This kind of interest in coinciding sounds is also present in Monastyrski’s text, The Autonomy of Art (1981), in which he describes how one day he simultaneously heard sounds of a vomiting person and the calling of a crow, and felt these were doubly interlocked (2009, pp. 188-189). This man seemed to feel an attachment to the crow, repeating synchronized sounds. Be that as it may, it is arguable whether such image of happy coincidence is kept in the actions of Collective Actions. Rather, the key phrase “Letov’s tails” might indicate restructuring in the seemingly integrated environment of the Soviet world.

In relation to this, it is worth emphasizing that enclosure by objects and the environment could be associated with the participants’ consciousness. Monastyrski seems to think that the surrounding environment can be a field that reflects participants’ consciousness. In other words, participants are enclosed by their consciousness.

Clearly, at this point in the “demonstration,” we are surrounded by a fairly large “field” of expectation, it is as if we have gone fairly deeply into it and away from the edges and have now closed in upon ourselves—in the same way that the thing that was being demonstrated to us was in reality a demonstration of our perception and nothing else.

(Monastyrski, n.d.-c)

It follows from this that his aim was to cause the emergence of a participant’s field of consciousness, built on a foundation of real environmental fields, and to connect the inside with the outside. This could mean that, to participants, these activities were also the objectification of their own consciousness as an outer event. A series of actions called Slogan displays these characteristics. In the first action from this series, Slogan-1977 (1977), a phrase from a collection of poems by Monastyrski—“I DO NOT COMPLAIN ABOUT ANYTHING AND I ALMOST LIKE IT HERE, ALTHOUGH I HAVE NEVER BEEN HERE BEFORE AND KNOW NOTHING ABOUT THIS PLACE”(Collective Actions Group, n.d.-d)—was quoted and placed among the trees in the forest as a slogan. Since this was only the fourth action performed by Collective Actions, this slogan could be interpreted as the externalization of the voice of the imagined participants who entered the place of action for the first time.

The series of slogans covers a broad range of contents, but Slogan-86 (1986) is the most notable among them. The action Slogan-86 consisted of burying objects such as a map and lights into a hole dug on a hill. After that, participants took two photos of the landscape: one that includes the place where things had been buried and another that did not include it within the frame. There was no material slogan. If so, what is expected as a slogan here? Surprisingly, it is the preface for the fourth volume of Journeys to the Countryside, a collected record of actions by Collective Actions, that was not present in the place of the action. In fact, the slogan exists outside the time and space of the action, despite the participant’s expectation that it would be there.

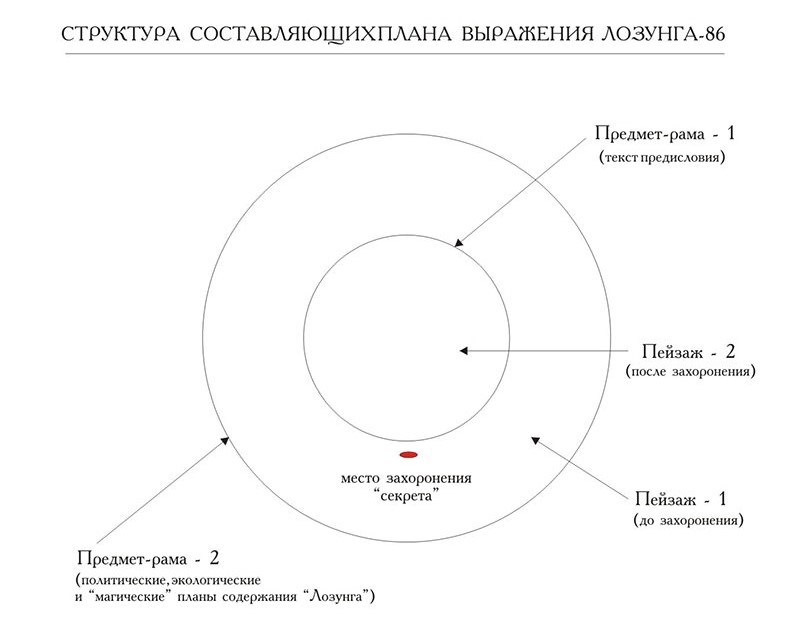

Figure 5. Illustration of the action, Slogan-86 (1986).

(from Collective Actions Group, n.d.-e)

Figure 5 explains the structure of Slogan-86. To interpret this structure, a chronological process must be considered rather than a spatial relationship among elements. First, the outmost circle is described as a “frame” for which explanations such as “politic, ecological, and ‘magical’ plans” are provided. Additionally, another “frame” is located within this frame, which is what this action treats as the slogan, namely, the preface for Journeys to the Countryside. “Landscape-1” is located between these “frames,” and it is written that “Landscape-1” predates the burying. Moreover, the location of burial for the objects such as a map and lights is shown as “the place of interment of the secret” in the area of “Landscape-1.” Lastly, in the center of the circles, there is “Landscape-2” which is explained as existence after burial. This structure is highly conceptual. However, if we consider the fact that the description of the action emphasizes temporal sequences such as before and after burial, it could be said that the figure shows the chronological process in which real landscape gets defined by several contexts. The landscape before burial is originally surrounded by “political, ecological, and ‘magical’” contexts, while taking a photo after burial is based on the concept of the “invisible slogan” (i.e., the preface that is invisible to participants). As such, that preface has some effect on the landscape as secondary context.

In any case, the preface written by Monastyrski was objectified as a component of the outer landscape and became the object of the line of sight as well as the field of consciousness that enclosed participants. This kind of intersection between the extended self and the outer nonhuman world with thing comes across like Pepperstein’s concept of the “thing-object.”

An approach to the problem of such externalization can also be observed in other actions like For D. A. Prigov (The secret oak-grove) (1992). This action is described below.

The participant (Prigov) and the action’s organizers (S. H. and A.M.) met at VDNKh metro station and took a trolley bus to the Botanical garden’s main gates. After approaching the eastern corner of the fence surrounding an oak grove, A.M. with a folder in his hands containing sheets from Prigov’s book “The catalogue of abominations” scaled up to size A2 detached himself from the group and while walking along the northern side of the oak grove rolled the sheets and put them on tops of the fence’s poles (each 100 meters approx.). This action was performed on the whole outer perimeter of the secret oak-grove’s fence and involved all 20 pages of the book.

After A.M’s having put on the first roll on the fence’s pole, Prigov and Haensgen followed behind him. Prigov took the rolls off the poles, unfolded them and read the verses aloud in front of S. H.’s video camera.

When the last sheet of the compilation was taken off (near the eastern corner of the grove, where the movement started), A.M. fixed the pages between two black cardboard sheets (the “front page” side was marked with an inscription “To D. A. Prigov”) and handed the such crafted big black notebook over to Prigov. (Collective Actions Group, n.d.-f)

At first, Prigov’s book left his side, taken apart into huge pages. Next, Monastyrski placed these pages on the poles which surround the secret place. After that, Prigov encountered his pages again as external objects in the outer environment. Pages of his book, once enlarged and in open air, must have been a different being before him. So, this indicates that the surrounding field could function as space into which their own consciousness and words are released. As such, we can observe that the Collective Actions group has sought to give expression to the fact that they were enclosed by objects and words, in ways that are somewhat different than Pepperstein’s observation on the death and life of terms as objects.

It is a fact that Conceptualism was a community without a uniform manifesto. However, sometimes we can also discover common traits in the activities of these artists. This paper tried to present a visualization of such common traits in Conceptualism. It could be said that observations of nature of things and human beings in Soviet life by pioneers (Yankilevsky and Kabakov) laid the groundwork for a more complex style adopted by the younger generation (Monastyrski and Pepperstein). Kabakov, of course, is well known as the artist who creates works full of words. However, it is worth mentioning that the younger generation allows both things and words the possibility of outward movement, closely connecting the problem of words with that of things.

That being so, a kind of externalization can be regarded as a shared feature of their vision. They have variously expressed the movement toward the outside: for example, radiation by Yankilivsky, deviation by Kabakov, “passo” by Pepperstein, and the use of the surrounding environment by the Collective Actions Group. These have a commonality in their tendency to break away from a ready-made environment.

Expression of their own ideas into the outside like slogans of the Collective Actions Group may be conjures images of expressive abstract paintings of the 1950s and 1960s. For instance, Bobrinskaya (2013, pp. 358-359) shows that reflective attitudes of conceptualists are not completely unrelated to the explosive nature of abstract paintings, comparing Kabakov and Lev Kropivnitsky, one of the central figures of Lianozovo. To put it briefly, she argued that the externalization of psychological impulse was one of the thresholds in conceptualists’ activities. However, it should be considered that the theme of externalization has been updated even in the following generation. For them, the movement of externalization does not mean mere explosion of an artist’s inner surface anymore. They do not inscribe their soul in medium, but rather seem to remove their own components from themselves to see them from another perspective with the help of things and the surrounding environment.

Historically speaking, it would appear that they shifted the tendency of Soviet unofficial art from the expression of an artist’s overflowing soul to the reflective externalization of the artist’s self through relationship with things. The voices of participants describing the impression of action were frequently recorded in the Collective Actions Group, which can be interpreted as a process of externalization. It may be the practice of talking about things by things that Pepperstein writes about. The issue of the analysis of such narrative should be addressed in further research.

Bobrinskaya, E. (2013). Chuzhie? Neofitsialnoe iskusstvo: mify, strategii, kontseptsii. Moscow: BREUS.

Chukhrov, K. (2012). "Soviet material culture and socialist ethics in Moscow Conceptualism”. Boris Groys (ed.), Moscow Symposium: Conceptualism Revisited (pp. 73-88). Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Collective Actions group. (n.d.-a). THE TENT. Retrieved from http://conceptualism.letov.ru/KD-ACTIONS-3.htm">

Collective Actions group. (n.d.-b). For N. Panitkov (Three darkness). Retrieved from http://conceptualism.letov.ru/KD-ACTIONS-13.htm

Collective Actions group. (n.d.-c). Music within and outside. Retrieved from http://conceptualism.letov.ru/KD-ACTIONS-31.htm

Collective Actions group (n.d.-d). Slogan-1977. Retrieved from http://conceptualism.letov.ru/KD-ACTIONS-4.htm

Collective Actions group (n.d.-e). Slogan-86. Retrieved from http://conceptualism.letov.ru/KD-actions-45.html

Collective Actions group. (n.d.-f). For D. A. Prigov (The secret oak-grove). Retrieved from http://conceptualism.letov.ru/KD-ACTIONS-64.htm

Degot, E. (2002). Russkoe iskusstvo XX veka. Moscow: Trilistnik.

–––. "Performing objects, narrating installations: Moscow Conceptualism and the rediscovery of the art object". E-flux Journal, November, Issue 29. Retrieved from https://www.e-flux.com/journal/29/68067/performing-objects-narrating-installations-moscow-conceptualism-and-the-rediscovery-of-the-art-object/

–––. (2012). "Performing objects, narrating installations: Moscow Conceptualism and the rediscovery of the art object”. Boris Groys (ed.), Moscow Symposium: Conceptualism Revisited (pp. 26-41). Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Groys, B. (2006). Ilya Kabakov: The man who flew into space from his apartment. London: Afterall Books.

Ioffe, D. (2013). "K voprosu o tekstualnosti reprezentatsii khudozhestvennoi aktsii moskovskogo kontseptualizma”. Tokarev, D.V (ed.), Nevyrazimo vsrazimoe: ekfrasis i problemy reprezentatsii vizualnogo v khudozhestvennom tekste (pp. 210-224, 225-229). Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie.

Jackson, M. J (2010). The experimental group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Kabakov, I. (2008). 60-70-e… Zapiski o neofitsialnoi zhizni v Moskve. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie.

Monastyrski, A. (2009). Esteticheskie Issledovaniya. Moscow: Library of Moscow Conceptualism.

–––. (n.d.-a). Finger. Retrieved from http://conceptualism.letov.ru/palets/MONASTYRSKI-FINGER.htm

–––. (n.d.-b). Dive Suits of Factography. Retrieved from

http://conceptualism.letov.ru/ANDREI-MONASTYRSKI-DIVE-SUITS-OF-FACTOGRAPHY.htm

–––. (n.d.-c). Preface to Volume One. Retrieved from http://conceptualism.letov.ru/MONASTYRSKI-PREFACE-TO-1-VOLUME.htm

Yankilevsky, V. (2003-a). "Memories of the Manezh Exhibition, 1962". Zimmerli Journal, Fall, No. 1, 66-77.

–––. (2003-b). I dve figury… Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie.

–––. (n.d.-a). Man in the Box. Retrieved from http://vladimiryankilevsky.com/cycle/early-works-2/attachment/1516/

–––. (n.d.-b). People in Boxes. Retrieved from http://vladimiryankilevsky.com/cycle/objects/a3-04-3/