DOI: 10.6667/interface.1.2016.26

Promoting GFL Student Engagement through

Skill-Heterogeneous Peer Tutoring

Wolfgang Odendahl

National Taiwan University

Abstract

This article is concerned with the effects of a specialized setup for student group work in L3 teaching. It promotes grouping students according to their skills in various subjects into heterogeneous groups as a way for inducing peer tutoring and raising student’s self-esteem. The motivation for this study sprang from an extra-curricular study project for subtitling German short films intended as a remedy for the widely observable study fatigue in Taiwanese German as a Foreign Language (GFL) majors. It turned out that combining students into workgroups couldn’t just rely on personal preferences, because the work required skillsets from three distinct areas: Project Management, Language, and Technology. As a solution to this kind of settings, this article proposes the instructor-organized creation of skill-heterogeneous workgroups. As theoretical background, it relies on findings from the fields of cooperative group work (e.g. Slavin, 2014; Cohen & Lotan, 2014, et al.), ability grouping and skill grouping (e.g. Missett, Brunner, Callahan, Moon, & Azano, 2014; Kulik & Kulik, 1992, et al.) in combination with motivational theories (e.g. Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Dörnyei, 2008; Reeve, 2009, et al.). The results of this project seem to indicate that the best way of grouping students was to assign each group an expert from one of the three main fields involved in subtitling. This way, every group member has authority in one field and can accept tutoring in the two remaining fields without losing face. The participating students enjoyed highly efficient group work that produced lasting synergetic effects in all areas involved.

Keywords: Group Work, Peer Tutoring, Student Engagement, Cooperative Learning, Placement

It is a commonplace observation in scholarly literature that Taiwanese students majoring in GFL often lack enthusiasm for their studies (cf. Lohmann, 1996, pp. 88–97; Plank, 1992; Chen, 2005, p. 29; Merkelbach, 2011, p. 130). This situation is linked to the fact that a substantial number of Taiwanese students choose their major not out of interest but because of their results in the centralized university entrance exam. Once enrolled though, students are initially willing to participate in classroom activities, often motivated by the impression that mastering a reputedly difficult language will improve their career options. Typically after three or four semesters, when they find that progress is slow and careers are not built on language skills alone, motivation drops. Students who lack motivation often simultaneously experience a lack of self-esteem with regard to their skills in German. This lack of self-esteem hinders their ability to establish meaningful social contact with their peers, which in turn leads to bad study habits and thus completes a vicious cycle.

While the main pedagogical objective of the project underlying this study was to raise study motivation,[1] this article focuses on the design of group work and its effects on student engagement. The project consisted of subtitling German short films and employing peer tutoring in small, skill-heterogeneous study groups. Its design combined current pedagogical psychology, such as internalization of motivation and Flow theory, with established group work techniques. Voluntary participants were 23 students majoring in German as a Foreign Language from a national Taiwanese university. Their mother tongue was Mandarin Chinese, with some using exclusively Taiwanese dialect at home; their English as well as their German proficiency level varied between beginner and intermediate. Teacher-Student classroom interactions were mostly in German, in-group interactions in Chinese. These Students were placed in skill-heterogeneous[2] groups and directed to perform autonomous small-group peer tutoring, the results of which were presented during regular classroom sessions. The project succeeded in fulfilling the commission of subtitling 14 German short films and organizing a public viewing. Participating students learned the basics of every skill involved in the process of subtitling, including (but not limited to) the importance of translation adequacy[3]. By utilizing group work concepts such as differentiation of tasks, co-constructive learning, and cognitive elaboration, the project achieved a significant rise in self-esteem and in the engagement of participating students.

The official goals set for the group work in the subtitling project were not directly related to formal German language learning but originated in a commission from Berlin short-film festival organizer interfilm GmbH. They consisted in completing Chinese subtitles for 14 German short films, booking a venue, and creating enough media attention to draw an audience to the event. Work groups were designed to include at least one member proficient in one of three skills necessary to complete the assignment, namely German-Chinese translation, video file manipulation, and event management. The educational goals of this project included developing and then passing on these skills but also aimed at increasing study motivation by providing students with the hands-on experience of applying their special knowledge to a marketable product. The project setting discussed in this article combines an inherently attractive and clearly defined high–stakes task with a skill-heterogeneous group design (cf. Wunsch, 2009, pp. 41–47) to cultivate several peer tutoring effects.

This paper consists of two parts, the first of which presents the conceptual framework and reviews the principles of motivational pedagogy underlying the project. Based on this theoretical framework, the second part discusses the practical application of these theories in the setup of the subtitling project.

1. Grouping Students for Cooperative Group Work

1.1 Group–worthy Tasks

The simple definition of the term motivation, as used in this paper, follows Reeve (2009), who describes motivation as the sum of all processes that lend energy and direction to behavior. The term skill is used in opposition to the term ability, skill being something that can be acquired through training, whereas ability is seen as static, either in the physical sense of being –for example– able to pronounce an s, or in reference to a point in time, e.g. being able to converse fluently in a foreign language (cf. Fleishman, 1964).

Cooperation has been proven to have positive effects on higher–level skills such as problem–solving and brainstorming, simply by increasing the number and quality of ideas produced (Slavin, 1980, p. 335). Lower–level skills requiring a certain amount of rote repetition, such as phonetic drills, are not likely to profit from group interaction. Successful group interaction depends on choosing complex tasks that require multiple skills to complete (Webb, 2008, p. 209). In order to get students to engage in high–quality talk, Cohen & Lotan (2014, pos. 330) stress the importance of the task’s inherent features: “the task needs to pose complex problems or dilemmas, have different potential solutions, and rely on students’ creativity and insights.” As a result, a well–designed task that requires several students to contribute to its solution enables their peers and teachers—but most importantly themselves—to recognize each group member as intellectually competent (Lotan, 2003, p. 73).

The key features of this particular group work design include interaction of group members in planning and performing tasks and stimulating interdependence with each other’s skill sets in heterogeneous groups. Short film subtitling provided an ideal setting for this project, since the medium is not only an important part of many students’ recreational activities but is also an area of work with a certain glamorous distinction from other jobs normally envisioned by graduates in the field of foreign languages (Odendahl, 2015, p. 138). The task of subtitling computerized movies meets the requirements of a complex task for a group of language students perfectly in that it consists in the combination of language–related content with strong technical elements. The language requirements for the technical parts are comparatively low, while adequately translating spoken German into Chinese subtitles requires a high degree of language competence (in both German and Chinese), register sensibility, and translation skills. In order to produce meaningful and adequate subtitles, translators not only have to thoroughly understand a given message and its intention in the established context but also think of an equivalent in their own language – especially since subtitles need to deliver the original message inside the confines of one line of text at a time. The translation task’s complexity makes the complete decoding of the source text and subsequent re–coding of the message in the target language an ideal environment for cooperative group work in the sense that cooperation will almost certainly yield better results than any individual effort (Slavin, 1980, p. 335). Although regarded in its entirety formidably complex, the task still remains achievable even for intermediate students, who may have to bolster their listening comprehension by playing a passage multiple times and factoring in any visual clues. Students can pause or manipulate the speed of a passage at any time until they can extrapolate every facet of every word uttered therein. Therefore the language skill requirements are high enough to make the task attractive, but not so high as to make it daunting (cf. Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 49), for students can confidently commit time to the solution of problematic passages in the certainty that these problems will be solved.

1.2 Benefits of Cooperative Group Work

The terms cooperative and collaborative are often used interchangeably for the same kind of group work; however, the definition of the term collaborative learning is very vague and may refer to “any pedagogical theory or method that advocates or involves using groups” (Smit, 1994, p. 69). This article uses the term cooperative as opposed to competitive and individualistic to refer to work that requires distinct efforts (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, p. 1). This usage is partly informed by the theories of the Russian psychologist Vygotskiĭ (1896-1934), which entered the American academic scene in the 1970s. Vygotskiĭ’s position that the benefits of cooperation occur when a more expert person helps a less expert person became mainstream consensus. Although Vygotskiĭan approaches to instruction usually concentrate on the transmission of skills from adult to child, as is the case in traditional classrooms, the process of negotiation and transformation is not necessarily limited to teacher-student interaction. The general principle of getting help from more competent persons includes the concepts of guided participation or scaffolding. Scaffolding enables any less competent person to carry out a task that s/he could not perform without assistance (Vygotskiĭ, 1978). For scaffolding to be effective, several conditions must be fulfilled. The help provided must be relevant to the student’s need; it must be correct, comprehensible, provided at the right time, and at the needed level. A certain learner autonomy is helpful, because according to the modern Vygotskiĭan school, learning is more than simply the transfer of knowledge from expert to novice; positive learning outcomes are more likely to occur if students use the help they receive to solve problems on their own without further assistance. This concept of learner autonomy after initial expert guidance was directly incorporated into designing the group work for this project. Scaffolding played an important role, too, but the concept had to be modified to fit the idea of peer tutoring with frequent tutor/tutee role switching, as discussed in the next paragraph.

The Vygotskiĭan conception is often contrasted to the Piagetian one, which centers on the child’s acquisition of knowledge rather than its unidirectional transfer from more competent members of society to less competent ones. For Piaget and his followers the notion of cognitive conflict (Piaget, 1923) occupies a central position. Cognitive conflict arises when learners perceive a contradiction between their existing understanding and what they hear or see in the course of interacting with others. Learning then occurs by reexamining their own ideas and by seeking additional information in order to reconcile the conflicting viewpoints. According to Piaget’s findings, children are more likely to exchange ideas with their peers than with adults, because peers speak at a level the others can understand and peers have no inhibitions of challenging each other.

In trying to marry the Vygotskiĭan concept of passing knowledge from a more competent person to another with the Piagetian insight of peers being more likely to understand and therefore influence each other, Hatano (1993, p. 155) developed the idea of co-construction of knowledge (cf. Webb, 2008, p. 204). Co-construction of knowledge postulates that knowledge is acquired as a construction process that occurs between learners. Hatano observes that one student can pick up useful information from other students who are not generally more capable. He also notes that some members involved in horizontal interaction can be more capable than others at a certain moment in time (Hatano, 1993, p. 157). This leads to the notion that the tutor/tutee roles can switch frequently—a notion that served as the foundation in designing the in-group interactions for the subtitling project.

Also crucial to the design of this peer tutoring setup was the concept of cognitive elaboration. It was employed by asking students to keep the small-group peer tutoring sessions short and to the point – the reasoning being that having a tight time frame leads to much more focused preparation work. Students would be limited to mere minutes for presenting their findings to their peers, who would then comment on the presentation and ask questions (see detailed description in the peer–tutoring section below). According to the theory, the very action of explaining something to others promotes learning, which essentially is the definition of cognitive elaboration. It should be noted that promoting cognitive elaboration by means of time pressure is not to be seen as separate from the Vygotskiĭan and Piagetian perspectives or the co–construction of knowledge, but as an integral part of them (Webb, 2008, p. 205). In order to make themselves understood, tutors need to rehearse their information and reorganize or clarify their presentation. Moreover, while formulating an explanation and thinking about the underlying problem, the dual process of generating inferences and repairing mental models is triggered.

1.3 Raising Enthusiasm through Cooperative Group Work

The main pedagogical mission of the subtitling project was to raise students’ enthusiasm for their GFL studies. [4] This section will give a brief summary of the motivational strategies fundamental to the project as a whole–including the choice of task, the grouping of students, peer tutoring, and the mix of autonomous work in small groups with classroom sessions.

The processes that give behavior its energy and its direction (and thereby define motivation) include the effects of increased self–esteem and positive interdependence, which are two major benefits of cooperative group work. The popular dualistic notion of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation does not fully do justice to the situation of Taiwanese GFL students, who generally have no interest in German language or culture before they enter university, but want to master the language once they begin their studies (Odendahl, 2015, pp. 117–118). So, instead of trying to raise levels of intrinsic motivation, a more fitting term for what this project tried to achieve would be the internalization of an initially extrinsic motivation. This concept has come to the attention of educational psychologists rather recently and lies at the foundation of many of today’s didactical techniques for promoting motivation in students.

Educational psychologists Ryan and Deci (2000, p. 54) observed that motivation not only rarely exists in pure intrinsic or extrinsic form but that it can also be created by outside influences. If initially extrinsic motivation undergoes the process of internalization, it will over time become very similar to intrinsic motivation. Deci and Ryan developed the Organismic Integration Theory—later merged into the influential Self Determination Theory—which postulates intrinsic needs of humans for competence and self–determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985, Chapter 5). In extension, Connell and Wellborn (1991, p. 51) state that any individual evaluates his or her status with respect to three fundamental psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Competence can be experienced when one’s own actions have positive outcomes and negative consequences are avoided. Autonomy is used in reference to the determination of goals, contents, and progress of their own learning activities. Additionally, the learner should also have some degree of initial interest in or curiosity about the task in order to be able to uphold a persistent autotelic occupation with it. As a result, picking the task of subtitling German short films for a project aimed at promoting motivation in 20–year–olds came rather naturally, since watching movies is one of the preferred pastimes of many Taiwanese students.

One of the prerogatives Ryan and Deci postulated for the process of internalization of motivation is that learners have to feel good about the actual study experience. This corresponds well with Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow theory, which defines Flow as an emotion that can be experienced when one is completely involved in an activity for its own sake and when one is using one’s skills to the utmost. The flow experience leads to better and more sustained learning (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 71) and is described by eight points (1990, p. 49), four of which were actively incorporated into the task design for this project, namely: clear goals that are challenging but attainable, the ability to concentrate on the task at hand, immediate feedback, and promoting a feeling of personal control over the situation and the outcome. Stoller and Grabe (1997, p. 13) emphasize that especially the engagement in challenging and increasingly complex tasks (which are still perceived as attainable) augments intrinsic motivation. They strongly recommend the combination of flow and Content-Based Instruction (CBI) – a term they use synonymously with Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) – for heightening motivation.

In summary, the above paragraph established the principles of cooperative group work with Self Determination and Flow theories as building blocks for effective group work. Finishing the theoretical framework of this article, the next two paragraphs will discuss peer tutoring and how to distribute students into groups for effectively making use of those components.

1.4 Peer Tutoring

Peer tutoring has several dimensions and may be evaluated with regard to what knowledge or which skills are to be taught, the ability level of tutors and tutees, role continuity (permanent or temporary), tutor characteristics, objectives of the program, and others (Topping, 1996, p. 322). It has been studied extensively and is proven to have significant benefits for learning as well as for promoting motivation and empowering students (Colvin, 2007, p. 3).

With regard to the literature which suggests that an increase in social interaction is associated with correspondingly increased benefits for student’s self–esteem (Goodlad & Hirst, 1989, p. 16), this project was designed to maximize social interaction as much as possible. The setup of small–group meetings had very few rules, one of which required physical meetings two times a week. Group members would work individually on a sub–task and give a short presentation on their progress for the benefit of the other members of the group. Each presentation should last five minutes, after which each of the listeners/tutees was required both to give positive feedback and ask one constructive question. Taking turns and switching the role of tutor/tutee when discussing different aspects or subtasks of the group’s common task was designed to stimulate respect for each other’s skills.

1.4.1 Cognitive Elaboration

Annis (1983) and others demonstrated that the way people conceptualize and organize things when they are learning something in order to teach it later is markedly different from when they are learning for their own use and the material is generally on a higher conceptual level. In other words, teaching what one has learned has a positive effect on one’s own learning (Webb, 2008, p. 205). Moreover, teaching to one’s peers has a better effect than summarizing for a teacher, as Durling and Schick’s (1976) study shows. “We formulate meaning through the process of conveying it. It is while we are speaking that we cognitively organize and systematize the concepts and information we are discussing” (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, p. 76). For their presentations, temporary tutors quickly learned to summarize tedious details, to focus their presentation on the more interesting problems they encountered, and to involve others in finding the solutions they suggested applying.

The positive effects of cognitive elaboration through peer tutoring were observed in regard of both the micro and the macro perspectives: In preparing to teach a subject to their peers, students not only needed to find a way to re–organize information and vocalize concepts, but also to reflect on the purpose of the whole while organizing their thoughts for teaching (cf. Goodlad & Hirst, 1989, p. 121).

1.4.2 Social Cohesion

Lotan (2003, p. 74) states that working on a tangible product—in our case a film with subtitles—helps create a positive interdependence between group members. According to Johnson & Johnson (1989, p. 61), a positive goal and interdependence are not enough on their own, and they insist that individual rewards are important if group work is to be effective. However, the subtitling project seems to provide evidence that this may not be as important as they believe: it did not offer any extrinsic or individual rewards besides the goal achievement itself. All members shared responsibility for the joint outcome, i.e., supplying adequate subtitles for the film they had chosen. They each took personal responsibility for contributing to the joint outcome as well as for teaching relevant skills to the other members (cf. Odendahl, 2015, p. 113). The level of interdependency and shared responsibility “adds the concept of ought to members' motivation -- one ought to do one's part, pull one's weight, contribute, and satisfy peer norms” (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, p. 63).

Through gaining respect for each other’s skills, peers can by extension build respect for the person. Johnson & Johnson (1989, p. 113) use the Freudian term “inducibility” for the receptiveness to each other’s suggestions and for the interpersonal attractiveness that results from frequent, accurate, and open communication. If group members realize that their success is mutually caused and that it relies on the contribution of each other’s efforts, they can build a shared group–identity, which should result in mutual support. Working together on a mutual goal results in an emotional bonding with collaborators, and, as a consequence, external rewards may not be necessary to promote motivation and achieve productivity, as long as group members provide respect and appreciation (cf. Johnson & Johnson, 1989, p. 73; 114).

1.4.3 Self–Esteem through Group Work

Johnson & Johnson (1989, p. 154) state that numerous studies have shown effective group work to increase self–esteem in participants. In our subtitling project, it was assumed that group members specializing in language would have higher group status and self–esteem than the others. With respect to raising self–esteem through the subtitling project, academic self–esteem was treated as being directly proportional to competence self–esteem (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, p. 161). By raising the latter, we hoped to simultaneously influence the former. In order to help students with comparatively lower self–esteem in regard to their academic achievements, skills other than translation were emphasized during the introduction and in classroom sessions. Especially in the initial small–group sessions, when members with computer skills were asked to help set up a foot pedal in combination with a special computer macro for transliteration, they had the chance to demonstrate their usefulness to peers with higher social status and subsequently muster the confidence to actively participate in discussions on other subjects, such as adequate translations. The experience of contributing to language tasks should lead to a virtuous cycle of boosting academic self–esteem with regard to their GFL studies.

Self–esteem is most eminently expressed while dealing with controversy. Peer discussions in general consist of challenging each other in a constructive but nevertheless controversial way. During the classroom sessions of the subtitling project, lively discussions revolved around different styles of translation for a given utterance in a certain situation. During the translation sessions, students tended to have very strong, but disparate, views of how to phrase a Chinese subtitle adequately. The relevant scholarship on work–group discussions suggests that friendly and constructive interaction is likely to result in interpersonal attraction. Moreover, if the process of working together on solving tasks is perceived as leading to either personal or mutual benefit, the readiness to comply with other people’s requests is increased (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, p. 116).

1.4.4 Learner Autonomy and the Teacher’s Role

Bruffee states that successful group work “provides students with a poly–centralized cooperative learning community which places faculty at the edge of the action, once they have set the scene, a position from which they may respond to needs which students discover for themselves” (1972, p. 466). This concept of changing the traditional teacher role from direct supervision to delegating authority has been widely accepted as a key feature of properly designed group work and harmonizes well with the notion of autonomy from motivational theories. For the subtitling project, the teacher set up a general framework for heterogeneous grouping and group interaction. After that, teacher interference was kept to the minimum of moderating classroom sessions and keeping an open door for student–initiated interaction. The actual work progress relied on autonomous group work.

Learner autonomy, important for Flow as well as for Self Determination (Ryan & Deci, 2000, pp. 59–60) is closely connected to splitting the goal into subtasks. Participants were free to choose their own time and method for solving whatever subtask was at hand at any one time, to experiment, play, discover, and learn while still having the reassuring presence of an overlying framework from project management. Even if a group would not meet the expectations for finishing a subtask by the next classroom attendance period, this would not jeopardize the project as a whole. True learner autonomy with a genuine feeling of control and self–determination includes the freedom to fail. In this setting, failing at a subtask meant spending time in the next classroom session on a discussion of the problems encountered and accepting solutions from the assembled peers. In other words, the stakes were low enough to permit experimenting, but participants would still strive to avoid the mild humiliation from having to expose one’s (perceived) shortcomings to the peer group.

1.5 Ability Grouping vs. Skill Grouping

1.5.1 Ability Grouping

Ability Grouping refers to the grouping of students homogeneously according to their demonstrated current performance level in the subject they are going to pursue (Missett et al., 2014, p. 248). It is used in tracking systems, a predominantly North American practice where stronger students are grouped together and receive different instruction than weaker students. By way of testing, the starting point and progress pacing for the students’ further studies are determined, and students are grouped accordingly. Research into the question of whether or not to group students by ability started in the early 20th century (Kulik & Kulik, 1992, p. 73). It mostly focuses on the impact of the practice on academic performance (effectiveness), equity, self–concept or self–esteem of students, as well as students’ or teachers’ attitudes toward the practice. Although there have been hundreds of studies and reviews on the topic of ability grouping, the discussion is ongoing, and findings are not universally conclusive (Kulik, 1992, p. viii; Hoffer, 1992, pp. 206–207). Major debates revolve around the questions whether teaching is more effective with homogeneously grouped students and whether all students (instead of just a certain group of students) benefit from the ability grouping arrangement, especially since in terms of equity, lower achievers in homogeneous groups may be deprived of the example and stimulation provided by high achievers.

It is an established fact that teachers’ expectations and preconceptions about their students’ performance influence the quality of instruction (Liu, 2014, p. 196; Missett et al., 2014, p. 256; Bernhardt, 2014, p. 38). Therefore, one major concern about ability grouping is that teachers who teach lower ability students are more likely to have lower expectations for them, which in turn might lead to lower–quality instruction. There seems to be a consensus that ability grouping generally helps academic achievement; provided that the course progression is adjusted to the requirements of each group and the teacher has adequately high expectations of the group. The greatest gains in student achievement from personalized pacing are noted when the curriculum is differentiated (Missett et al., 2014, p. 250; Brulles, Saunders, & Cohn, 2010, p. 346; Neihart, 2007, p. 336). These findings are true for all kinds of grouping, but Kulik & Kulik (1992, p. 76) especially stress the positive effects of differentiated education for within–class grouping of students.

1.5.2 Skill Grouping

Because ability grouping is very common and literature on skill grouping scarce, I had to rely on findings from studies on the former to assess the feasibility of the latter with respect to the goal of raising students’ self–esteem and study motivation. The major difference between the grouping used in the subtitling project and ability grouping is that of homogeneity versus heterogeneity in group composition. Ability grouping aims at assembling members with similar abilities into homogeneous groups in order to further the very ability that served as the selection criterion. In contrast, what I call skill–heterogeneous grouping matches students with different skill sets in order to exchange those skills via peer tutoring, so that in the end all participants will be able to master all skills involved. In the setting of the subtitling project, skill–heterogeneous grouping was designed to cultivate co–constructive learning and cognitive elaboration, as well as social cohesion and self–esteem. There is strong evidence that the positive effects of peer tutoring in heterogeneous groups are reciprocal for tutors and tutees, since students gain significantly from peer teaching by preparing elaborated explanations for other students and thus creating the effects linked to cognitive elaboration (Webb, 2008, p. 205).

Differences aside, there are some major proven benefits of ability grouping that can safely be assumed to be valid for skill grouping also. These include the influence of teachers’ expectations for students’ success, the importance of differentiating tasks in order to match each student's personal skills and abilities, as well as the adequacy of the task in regard to both each student’s needs and the achievement of the task's goal. According to the above theories, differentiated and adequate tasks combined with high teacher expectation should lead to improved learning. The presence of high achievers should positively influence lower achievers in the right setting, and peer tutoring effects in heterogeneous groups should benefit both tutor and tutee. Overall, it was expected that the cooperative work would have positive effects on the participant’s self–esteem, motivation, and study habits.

2. Setting of the Subtitling Project

The subtitling project involved several layers of groups, including informal ad hoc groups during preparation, skill–heterogeneous small work groups, and the plenary meeting of all participants. The concepts of a) co–construction of knowledge, b) cognitive elaboration, and c) peer tutoring with tutor/tutee role–switching were the core components for the group work design in the subtitling project. This setup could be expected to trigger the beneficial effect of group cohesion, which occurs when students want to help each other because they care about the group and its members (cf. Clément, Dörnyei, & Noels, 1994, p. 424). In order to enable group cohesion, cooperative learning methods should include the development of interpersonal skills, in particular, active listening, stating ideas freely, as well as social small–group skills (Webb, 2008, p. 205). Accordingly, weekly classroom sessions were set up to promote brainstorming and mind–mapping, hoping that the spirit of uninhibited discussion would spread to the autonomously acting small groups.

Three outcomes of cooperative learning were emphasized in this project: academic motivation, group cohesion, and self–esteem. These outcomes are interconnected and will only be marginally approached in this paper, which focuses on group design. The following section describes the general setup designed to enhance the first two of the above outcomes, and reasons why a boost in self–esteem should follow.

2.1 Effective Cooperation through Group Work and Task Design

Group cohesion should lead to increased self–esteem; therefore, the group work in this project was designed to promote group cohesion inside small workgroups as well as in the larger group of all project participants. Properly designed group work verifiably produces positive results, with high–, medium–, and low–achieving individuals all benefiting academically from participating in heterogeneous cooperative learning groups (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, p. 47; Goodlad & Hirst, 1989, p. 84). Nevertheless, not every task and not every teaching goal are suited for group work. The Johnsons’ model of cooperative learning states that five criteria must be satisfied for instruction to qualify: positive interdependence, individual accountability, face–to–face promotive interaction, teamwork skills, and group processing (Johnson & Johnson, 1999, pp. 82–83). The main question discussed in this section is the setup of group work with tasks that make use of cognitive elaboration and that allow co–construction of knowledge as well as frequent role switching between tutors and tutees.

There are differences between learning groups and work groups with different goals being attached to group work. However, there are some common design factors that influence the chance of group work being successful. In order to create an environment in which effective cooperation can occur, three areas must be addressed: group creation (including size and homogeneity), the design and implementation of structured activities, and appropriate facilitation of group interaction (Graham & Misanchuk, 2004, pp. 190–196). It seems to be crucial to carefully evaluate teaching goals for suitability and pay minute attention to the design of tasks that can be deemed group–worthy by the amount of work involved and by the tasks’ inherent complexity.

In order to incorporate these theories into the subtitling project, the main task had to be split into smaller subtasks (see below). Group interactions consisted in a mix of individual work and peer tutoring. Subtasks were set up to be worked on individually by mastering the appropriate skills and then passing on those newly acquired skills to peers in small tutoring groups (cf. Büttner, Warwas, & Adl-Amini, 2012, pp. 2–3). In the past, peer tutoring as a form of cooperation has most often been associated with written composition. Generalizing from current definitions of cooperative writing, cooperative group work may be described as situations in which members of small groups engage in a common task, cooperate intensively, make all process decisions collectively, and where the group as a whole takes responsibility for the outcome (cf. Bosley, 1989, p. 6; Ede & Lunsford, 1990, p. 15).

The method employed here could be described as a variety of the jigsaw method. Each group member is assigned a part of the project which is essential to the finishing of the project (Slavin, 1980, p. 320). While constructively challenging another person’s view leads to more active participation and to greater identification with the outcome (Johnson & Johnson, 1989, p. 70), destructive controversy might jeopardize all beneficial effects of peer tutoring and effectively poison the interpersonal relationships of group members, especially so, as members with stronger self–esteem might try to use coercive means to achieve their goals. It was therefore crucial to have an effective set of rules for interaction during peer discussions and to establish a climate of respectfulness and reciprocal support. For small–group discussions, the rules were established as follows:

1. Small–group meetings are twice a week; every member presents every time.

2. Allocate exactly five minutes for each presentation and moderated discussion.

3. Tutors present clearly, to the point, and use at least two adequate visual aids.

4. Tutees must pay respectful attention and take notes.

5. Tutees must give at least one positive comment and ask one constructive question concerning the contents of the presentation before criticizing.

After one such round of presentations, groups were free to continue discussing, socialize, or do whatever they wanted. For the classroom sessions, where mostly the teacher played the role of moderator and the presenting groups acted as single entities, rules had to be more flexible, while still upholding the principle of constructive and respectful criticism. This specific group work mode—combining individual effort with group sessions—represents a new combination of established practices.

2.1.1 Splitting the Task

Fearing that the ultimate goal of presenting 14 German short films with Chinese subtitles to a Taiwanese audience might seem too broad and intimidating, and in order to prevent the demotivating effect of a looming deadline for a large and unfamiliar task, the process had to be broken into smaller, more specific subtasks that presented short–term objectives (see Odendahl, 2015, p. 129). These were designed to correspond to one of the three skill–sets represented by at least one member in each group.

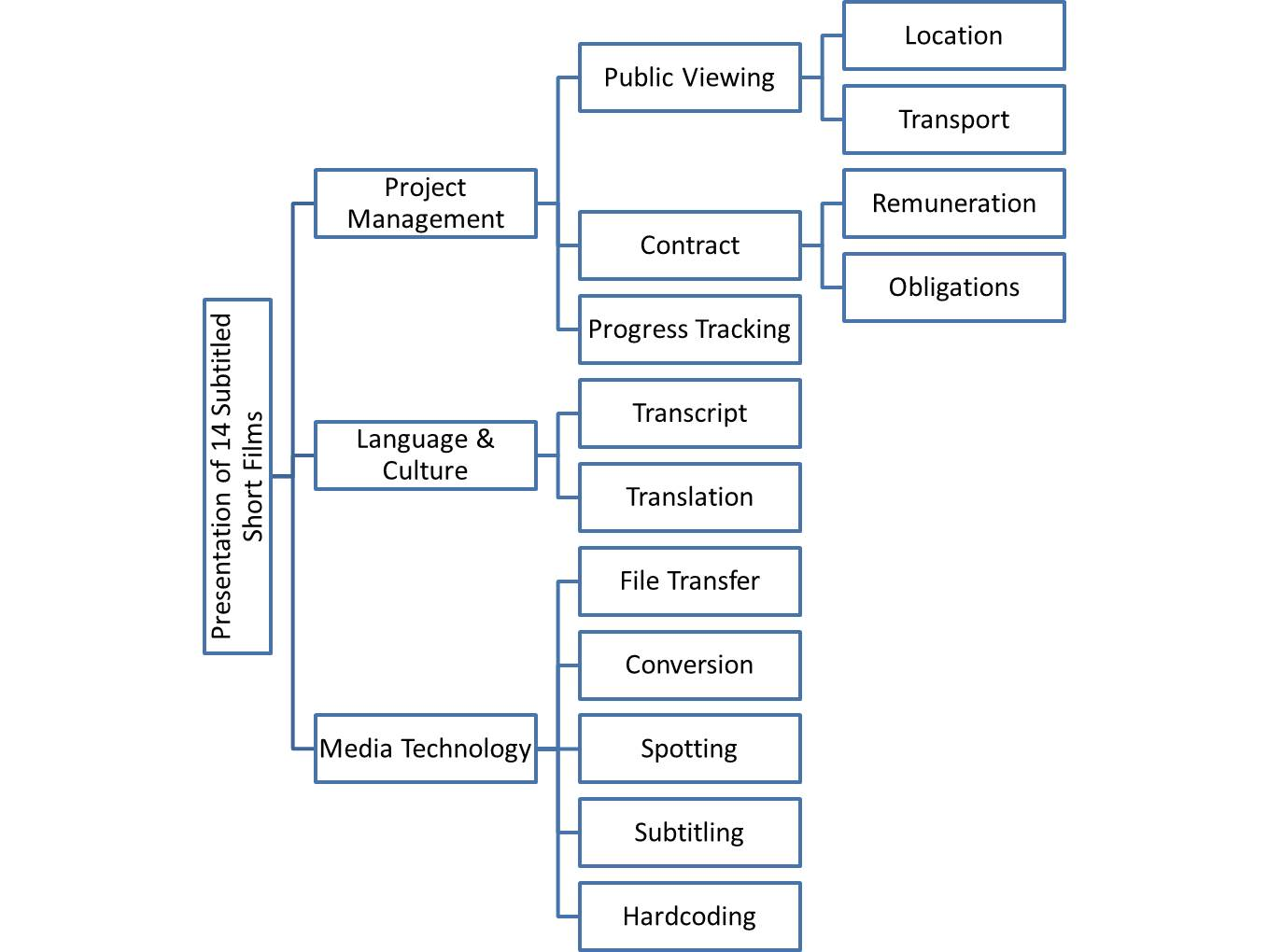

The public screening of German short films with Chinese subtitles involves three major fields of preparatory work. The most visible part consists in adequately translating the spoken originals into short written passages. The second part involves a considerable number of technical aspects, which are all crucial for the successful completion of the task. These include FTP file transfers, file format conversions, mastering unfamiliar software, and building an educated opinion of using softcoded versus hardcoded subtitles. The third part of the project was the event management, which included negotiating contract terms and keeping track of the progress of the project as a whole.

Fig. 1: Task Explanation Chart

(For ease of reference, the following explanatory text uses capitalization to indicate the corresponding nodes.)

The main goal, Presentation of 14 Subtitled Short Films, is achieved by the cooperation of group members specializing in Project Management, Language & Culture, and Media Technology. The tasks in the field of Project Management are twofold, concerning the Public Viewing as well as the Contract. Subtasks for the Public Viewing include securing a Location and organizing Transport. The terms of the Contract have to specify Remuneration and Obligations. Members specializing in Language & Culture will have to compose a Transcript of every word uttered in the films, which would subsequently have to undergo Translation. Team members specializing in Media Technology arrange the File Transfer via FTP and administer Conversion so that the files can be manipulated with the specialized subtitling software. During Spotting, appropriate time points for the beginning and end of showing each subtitle on screen are determined. The Subtitling process involves breaking the translation into parts that fit on the screen and writing those in a file with time stamps next to each subtitle. In a final step, Hardcoding combines the subtitles and the film into a single computer file in order to make sure the film can be played from any device.

Knowing my students and their study background intimately, I decided to employ some tweaks in order to prevent students with good language skills from dominating the group work. In order to make the technical aspects appear more attractive and challenging, special attention was drawn to every step of computer file manipulation. Furthermore, only freeware or open source software programs were to be used during the project. The reasoning for this requirement was that in order to build a real–life skill which any participant could readily offer to potential customers, students should not be forced to invest money in specialized software programs before their business has even started.

As discussed in the theoretical framework, the internalization of external motivation requires the task to make the learner think of it as challenging but attainable (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 49). Dividing the assignment into more manageable subtasks and assigning these to designated roles inside the work groups provided students with weaker language skills the opportunity to play an equally integral and meaningful part in the project.

Most of the subtasks have their own intricacies to be explored and subsequently shared by the group member acting as moderator for that skill area. After having participated in the project, every student could expect to have sufficient expertise in all steps necessary to independently and professionally offer subtitling services to customers. The following sections will deal with the organizational aspects of the group work from a didactical point of view, with special attention to facilitating in–group peer tutoring.

2.1.2 Selection and Placement of the Participants

In order to find students who were genuinely interested in the project, a two–stage online application form in combination with an online language test was used. At the end of the first page of the online application form, candidates were asked to enter their score from a separate online language test. Only participants who filled in a minimum score from the language test were taken to the second stage of the application and issued an invitation to the initial information meeting. Although a show was made of checking attendance at the beginning of the meeting, the main purpose of this arrangement was to either attract participants whose language competency was above a certain level, or at least such students motivated enough to cheat on their score. From the 40 students who came to the initial information session, 23 stayed after the short break that was purposely arranged between project explanation and the forming of work groups. Three more participants left before the project was finished. None of the participating students had prior experience with the processes involved in subtitling. The participants who professed themselves as technically inclined mostly knew how to edit videos on their computers, but none of them had ever even thought of subtitling. Similarly, students who thought of themselves as more proficient in German than their peers had some experience with translating short text passages during German class, but never formally thought of translation as a service to readers who do not understand the original.

The grouping aimed at creating small skill–heterogeneous groups with three distinct areas of expertise (cf. Fig. 1) as discussed in the last paragraph. In the introductory session, after having been informed of the nature of the task and given the chance to use a short break to leave without losing face, participants were asked to physically move to one of the areas in the room labeled German, Computer, or Project Management. During task explanation, they had learned that the nature of their group work would be to assume responsibility for one area, doing individual work on the parts manageable by one person alone, identifying difficulties, exploring solutions, and preparing a report on that subtask for the other members. An appointed moderator would streamline the efforts of the whole group for those parts of the task which required cooperation with the other members of the group.

In the group-formation process, I could observe that participants confident enough to choose translation aimed to put their skills to work in a challenging, interesting, and GFL–related way. Students who chose to be technical experts of their groups mostly did not feel comfortable with their German proficiency but had some confidence in their computer skills. Those who chose to be in project management often did not feel confident enough in either one of the other two areas. In some cases, they just wanted to be part of a group on the basis of personal affection.

Since all participants majored in German as a foreign language, those who chose to be moderators for transliteration and translation were also the ones with stronger self–esteem, often playing leading roles in the regular German classroom. There, they perceived themselves as successful and were acknowledged by their peers. These students showed no lack of motivation for their studies, had a generally positive attitude towards curricular and extra–curricular activities, and were mostly willing to help other students – as long as they were treated as academic higher–ups. During the project, one of the challenges for peer tutoring was to get those students to acknowledge other group members’ superior skills in other fields, which were equally important for the successful completion of the project.

As pointed out by Cohen and Lotan (2014, pos. 829), skill–heterogeneous groups, provided they work well, eliminate the undesirable domination of a group by an expert member. By taking turns at being the experts, group members break up the hierarchy established by academic status in favor of mutual respect. One of the findings of this project was that if skill–heterogeneous groups are to work well, then special attention needs to be paid to reducing the gap between high–status and low–status students' participation rates. Especially the design of project– or event–management tasks has to be carefully constructed so as to facilitate inter–skill exchanges.

2.1.3 Structuring Activities, Facilitating Interaction

Effective cooperation requires skills in leadership, trust, decision–making, and conflict management. Because of the time constraints of one two–hour plenary meeting a week a formal training in all required social skills was not feasible. In order to prevent counterproductive behavior, the teacher instead provided instructions on how to give respectful negative feedback and urged groups to stick to a set of simple interaction rules during their peer tutoring sessions. These instructions included the allocation of five minutes of uninterrupted talk time to each (temporary/revolving) tutor and the recommendation to start and end each member’s feedback with a positive remark concerning the contents or presentation of the talk, before going into specifics.

The subtitling project consisted of several modes of group work. Individual participants would work alone or cooperate in virtual space, often with members of other groups. They met twice a week in small groups of three or four members, each of whom paid attention to different subtasks. In weekly classroom meetings with all groups present, peers would review the results of the groups’ efforts. Although Johnson & Johnson (1989, p. 42) find significant evidence that pure cooperative work yields better academic results than forms that mix cooperative with individualistic work, the approach of individualistic learning with subsequent peer tutoring promised adequate results with benefits in regard to self–esteem and group consensus between members with very distinct skill sets, especially since the subtitling project was extracurricular and participants were sometimes hard put to set up a physical meeting (cf. Odendahl, 2015, p. 123).

The group work was designed to distribute responsibilities and cooperation through communication in the form of reports and structured discussions. Small–group interaction in the form of regular meetings was to take place not less than twice a week, each meeting scheduled to last 15 minutes or more. During the in–group discussions of problems and solutions, moderating members would act as tutors, passing their insights on to the other members in structured reports and asking them for support with specific problems. In the spirit of cognitive elaboration, learning not only occurred through peer tutoring, but also during the process of organizing and preparing reports in a manner the other members would understand.

Motivation–inducing interaction was first realized within the small group by tutees giving constructive face–to–face feedback and also during classroom sessions by the teacher’s encouragement of each group’s overall performance and his giving informational feedback regarding each member’s learning achievement. Aside from cooperating in small groups, participants were expected to join weekly classroom attendance periods. These followed the same basic principles as the small–group meetings, with the groups replacing individual members as the basic entity of interaction and the teacher taking the role of moderator. Classroom language was mostly German on the part of the teacher and predominantly Chinese among the students. The focus of classroom interaction was on summarizing progress, the inter–group exchange of problems and solutions, and, most importantly, the peer review of finished subtitles.

The highlight of most classroom attendance sessions was the screening of a subtitled film (or section thereof), where the audience would objectify their first impressions with a prepared mini–questionnaire using a forced–choice four point Likert scale.

Translation Adequacy ....................... bad ◯ ◯ ◯ ◯ good

Spotting ................................... bad ◯ ◯ ◯ ◯ good

Readability of Subtitles ................... bad ◯ ◯ ◯ ◯ good

Overall Viewing Experience ................. bad ◯ ◯ ◯ ◯ good

Tips:

......................................................................

......................................................................

......................................................................

Fig. 2: Peer Review Questionnaire

Before using the questionnaires for the first time, classroom time was devoted to the explanation of the technical terms it contained. Students knew that Translation Adequacy evaluated the naturalness of the translated wording in that particular context. The question they should ask themselves was: if that person were Taiwanese, would s/he use that term in this situation? Spotting concerns the timing of beginning and ending of the subtitles, which should correspond to the lip movement of the actors. By Readability of Subtitles, we understood the equilibrium between duration of subtitle and amount of information involved. For considering the Overall Viewing Experience, students had to judge whether a Taiwanese audience would experience the same feelings as the originally intended target group. In the Tips section, students could make some notes that they would refer to in the plenary discussion which followed immediately after the screening. The questionnaires were collected after the discussion and passed to the group responsible for that film.

Several of the high achievers in German thoroughly enjoyed the process of working on finding the most adequate translation for colloquialisms. During classroom sessions, group cooperation was realized by the presenting group paraphrasing the German original for the plenum, and pointing out the literally translated meaning, as well as the contextual meaning within the film’s plot. After every member of the audience understood the intricacies of that particular passage, all of them were equally able to contribute to an adequate rendering in Chinese. This meant that many of the more colloquial subtitles were truly the product of a lively and pleasant group brainstorming, during which ludicrous slang was discussed alongside overly formal speech as well as literary translations and so on. Discussions of the adequacy of translations were also the highlights in classroom sessions, where the plenum often polished the finer points of the Chinese renderings.

3. Observations

The current literature on cooperative learning comprises a vast amount of qualitative and quantitative data. For the years between 1898 and 1989, Johnson & Johnson (1989, p. 16) count 521 studies on “the relative impact of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic situations on a wide range of dependent variables, including achievement and productivity, motivation to achieve, intellectual and creative conflict, quality of relationships, social support, self–esteem, and psychological health.” The data, mostly collected in controlled environments, proves unanimously that cooperative learning, if deployed on group–worthy tasks, is superior to its individualistic or competitive variants with respect to academic achievement and positive effects on study motivation. Given this abundance of evidence, there was no reason for this study to set out replicating these findings; instead, it was designed to find out whether collaborative learning in small, skill–heterogeneous groups employing peer tutoring can help Taiwanese GFL students master a complex task and regain a positive attitude towards their studies and towards themselves.

The crucial point discussed in this paper is the setup of skill–heterogeneous group work with a group–worthy task, i.e., a task challenging and complex enough to justify the involvement of several members at once. Subtitling German short films seemed to be near perfect, since it is a rather challenging endeavor from both its technical aspects as well as the translator’s point of view. What might have helped even more is the fact that all participants had a very positive attitude towards the medium, which of course is part of most students’ daily consumer experience – foreign films on Taiwanese TV are subtitled. Still, even in the age of YouTube and 30–second advertising clips, the short film is an art form with its own rules for epic storytelling with which most participants had never before come in contact. Similarly, even though subtitles are very common on Taiwanese television, consumers normally don’t realize the intricacies involved in formulating sentences that fit a standard screen width or in synchronizing the appearance of subtitles with the actor’s lip movement. However, by taking part in the project, students gained knowledge of these intricacies through hands–on experience, and so creating subtitles for short films became a challenging and rewarding task for them.

The small–group peer tutoring rules, which explicitly ask participants for sharing their newly acquired skills and insights in a structured way, enable cognitive elaboration. Furthermore, the frequent switching of tutor/tutee roles is crucial for the intended effects of reciprocal skill appreciation. In the beginning, not everybody was comfortable with their roles as peer tutors/tutees, neither in structuring their knowledge nor in constructively discussing solutions as equals. This initial awkwardness passed rather quickly through repetition, because every non–virtual session of group work, including classroom sessions, would include presentations followed by discussions. Rather unsurprisingly, some of the lower–achieving students who would not actively participate in regular German classroom settings gained self–esteem through respect from their peers by showing exceptional computer skills which were directly applicable as a solution to problems at hand. The internal hierarchy of these groups flattened notably and the atmosphere of group discussions became more animated and cordial; the group cooperation in a flattened peer hierarchy was an important new experience that helped students experience social interdependence in pursuing a complex task. The newly gained self–esteem of formerly shy students spilled into their general behavior even in regular German class, which was completely unrelated to the project and most of its tasks.

The success of the project shows that one of the prerogatives for skill–heterogeneous groups to work well is reducing the gap between high–status and low–status students' participation rates. The synergetic effects of group work were not limited to the formerly lower achievers. As predicted by the literature, intense group work with peer tutoring led to a deep understanding of the subject matter as well as social cohesion in and between groups.

After participating in the project, all students had a clear understanding of the processes and subtasks involved in subtitling films and organizing a public viewing. This included transliterating, translating, and several file conversions and manipulations. Of course, the details and challenges in delivering high–quality work were understood most clearly by the members who had explored that particular area themselves, but through the small–group and classroom reports, everybody had at least an idea of the intricacies involved. More significantly, they included a profound understanding of the underlying principles of translation adequacy (see Reiß, 1984), the importance of timing subtitles in accordance with the video picture (‘spotting’ cf. Mälzer-Semlinger, 2011), general subtitle conventions (cf. ARD Das Erste, 2014), and customer–oriented planning.

Overall, the project and its work group design turned out to be very effective in keeping work progress on track while simultaneously facilitating social cohesion and mutual respect. The division of the project into subtasks and the completion of multiple subtasks helped participants perceive competence, a prerogative for the Flow experience (cf. White, 1959, p. 297; Deci & Ryan, 1985, p. 40; Connell & Wellborn, 1991, p. 51). Another factor for nurturing the perception of competence came from assigning specific skill areas to each group member, so that everybody was given the opportunity to tutor the other members in one particular area. Students learned to give concise and structured reports of their work, take responsibility, plan inside a given time frame, meet deadlines, organize their group work, and communicate their work’s progress with people outside their own skill set. All students said they especially enjoyed the fact that they had been able to use their skills in a real life application. On a personal level, several new friendships emerged between students with different skill sets who without the peer tutoring experience would probably not have recognized the other’s talents. Evaluating these results, I propose introducing skill-heterogeneous peer tutoring into general classes as part of a mix of motivational devices.

References

Annis, L. F. (1983). The Processes and Effects of Peer Tutoring. Human Learning: Journal of Practical Research & Applications, 2(1), 39–47.

ARD Das Erste. (2014, February 25). Gestaltung von Untertiteln. Retrieved 3 March 2014, from http://www.daserste.de/service/kontakt-und-service/barrierefreiheit-im-ersten/gestaltung-untertitel100.html

Bernhardt, P. E. (2014). Making Decisions about Academic Trajectories: A Qualitative Study of Teachers’ Course Recommendation Practices. American Secondary Education, 42(2), 33–50.

Bosley, D. (1989). A National Study of the Uses of Collaborative Writing in Business Communications Courses among Members of the ABC. Illinois State U.

Bruffee, K. A. (1972). The Way Out: A Critical Survey of Innovations in College Teaching, with Special Reference to the December, 1971, Issue of College English. College English, 33(4), 457–470.

Brulles, D., Saunders, R., & Cohn, S. J. (2010). Improving Performance for Gifted Students in a Cluster Grouping Model. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34(2), 327–350.

Büttner, G., Warwas, J., & Adl-Amini, K. (2012). Kooperatives Lernen und Peer Tutoring im inklusiven Unterricht. Zeitschrift Für Inklusion, 1(2). Retrieved from http://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusion/article/viewArticle/147/139

Chen, Y.-H. (2005). Deutsch als Tertiärsprache in Taiwan. Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Chinesischen als L1 und des Englischen als erster Fremdsprache (Ph. D. Dissertation). Hamburg, Hamburg.

Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. A. (1994). Motivation, Self‐confidence, and Group Cohesion in the Foreign Language Classroom. Language Learning, 44(3), 417–448.

Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (2014). Designing Groupwork: Strategies for the Heterogeneous Classroom (Kindle Edition). New York: Teachers College Press.

Colvin, J. (2007). Peer Tutoring in Higher Education: The Social Dynamics of a Classroom. Saarbrücken: VDM.

Connell, J. P., & Wellborn, J. G. (1991). Competence, Autonomy, and Relatedness: A Motivational Analysis of Self-System Processes. In M. R. Gunnar & L. A. Sroufe (Eds.), Self Processes and Development, 43–77. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum.

Dörnyei, Z. (2008). New Ways of Motivating Foreign Language Learners: Generating Vision. Links, 38, 3–4.

Durling, R., & Schick, C. (1976). Concept Attainment by Pairs and Individuals as a Function of Vocalization. Journal of Educational Psychology , 68(1), 83–91.

Ede, L. S., & Lunsford, A. A. (1990). Singular Texts/Plural Authors: Perspectives on Collaborative Writing. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Fleishman, E. A. (1964). The Structure and Measurement of Physical Fitness. Oxford: Prentice-Hall.

Goodlad, S., & Hirst, B. (1989). Peer Tutoring. A Guide to Learning by Teaching. ERIC.

Graham, C. R., & Misanchuk, M. (2004). Computer-Mediated Learning Groups: Benefits and Challenges to Using Groupwork in Online Learning Environments. In Online Collaborative Learning: Theory and Practice (Vol. 1, 1–202). Hershey: IGI Global.

Hatano, G. (1993). Time to Merge Vygotskian and Constructivist Conceptions of Knowledge Acquisitions. In E. A. Forman, N. Minick, & C. A. Stone (Eds.), Contexts for Learning: Sociocultural Dynamics in Children’s Development, 153–166. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hoffer, T. B. (1992). Middle School Ability Grouping and Student Achievement in Science and Mathematics. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14(3), 205–227.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooperation and Competition: Theory and Research. Edina: Interaction.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1999). Learning Together and Alone: Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic Learning (5th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Kulik, J. A. (1992). An Analysis of the Research on Ability Grouping: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Storrs, CT: National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented.

Kulik, J. A., & Kulik, C.-L. C. (1992). Meta-analytic Findings on Grouping Programs. Gifted Child Quarterly, 36(2), 73–77.

Liu, H. (2014). Questioning the Stability of Learner Anxiety in the Ability-Grouped Foreign Language Classroom. The Asian EFL Journal Quarterly, 191.

Lohmann, H. (1996). Die deutschen Abteilungen an den Universitäten in Taiwan und ihre Studenten: zur Lage des Deutschunterrichts an den Universtäten und ausseruniversitären Institutionen in Taiwan im Kontext des chinesischen Bildungssystems und zur Studien- und Lebenssituation der Studenten an den deutschen Abteilungen . Münster; New York: Waxmann.

Lotan, R. A. (2003). Group-Worthy Tasks. Educational Leadership, 60(6), 72.

Mälzer-Semlinger, N. (2011). Bild-Text-Beziehungen beim Filmübersetzen. Lebende Sprachen, 56(2), 214–223.

Merkelbach, C. (2011). Wie unterscheiden sich die Lernstrategien beim Erlernen von L2 und L3? Ergebnisse einer empirischen Studie bei taiwanischen Deutsch-als-L3-Lernenden. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 16(2), 126–146.

Missett, T. C., Brunner, M. M., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., & Azano, A. P. (2014). Exploring Teacher Beliefs and Use of Acceleration, Ability Grouping, and Formative Assessment. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37(3), 245–268.

Neihart, M. (2007). The Socioaffective Impact of Acceleration and Ability Grouping: Recommendations for Best Practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 330–341.

Odendahl, W. (2015). CLlL-Projekt zur chinesischen Untertitelung deutscher Kurzfilme als Mittel zur Motivationsförderung. In C. Merkelbach (Ed.), Mehr Sprache(n) lernen - mehr Sprache(n) lehren, 117–142. Aachen: Shaker.

Piaget, J. (1923). Le langage et la pensée chez l’enfant. Études sur la logique de l’enfant (3; 1948). Neuchâtel, Paris: Delachaux and Niestlé.

Plank, J. (1992). Deutschstudium in Taiwan. Taiwan Heute (= Freies China 11.12, S. 23-30), 6(5). Retrieved from http://taiwanheute.nat.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=68135&CtNode=1663&mp=22

Reeve, J. (2009). Understanding Motivation and Emotion (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Reiß, K. (1984). Adäquatheit und Äquivalenz. In Die Theorie des Übersetzens und ihr Aufschlußwert für die Übersetzungs-und Dolmetschdidaktik. Akten des Internationalen Kolloquiums der Association Internationale de Linguistique Appliquée AILA, Saarbrücken, 161–176. Tübingen: Narr.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. http://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Slavin, R. E. (1980). Cooperative Learning. Review of Educational Research, 50(2), 315–342.

Slavin, R. E. (2014). Cooperative Learning and Academic Achievement: Why Does Groupwork Work? Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 785–791.

Smit, D. W. (1994). Some Difficulties with Collaborative Learning. In G. A. Olson & S. I. Dobrin (Eds.), Composition Theory for the Postmodern Classroom, 69–81. New York: SUNY.

Stoller, F. L., & Grabe, W. (1997). Content-Based Instruction: Research Foundations. In S. B. Stryker & B. L. Leaver (Eds.), Content-based Instruction in Foreign Language Education: Models and Methods, 5–21. Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press.

Topping, K. J. (1996). The Effectiveness of Peer Tutoring in Further and Higher Education: A Typology and Review of the Literature. Higher Education, 32(3), 321–345.

Vygotskiĭ, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Webb, N. M. (2008). Learning in Small Groups. In T. L. Good (Ed.), 21st Century Education: A Reference Handbook, 203–211. New York: SAGE Publications.

White, R. W. (1959). Motivation Reconsidered: The Concept of Competence. Psychological Review, 66(5), 297–333.

Wunsch, C. (2009). Binnendifferenzierung. In U. O. H. Jung (Ed.), Praktische Handreichung für Fremdsprachenlehrer (5th ed., 41–47). Frankfurt / M.: Lang.

[1] The issue of raising study motivation is being dealt with in full detail in „CLlL-Projekt zur chinesischen Untertitelung deutscher Kurzfilme als Mittel zur Motivationsförderung“ (Odendahl, 2015).

[2] The term is central to my thesis and will be discussed in detail throughout the later paragraphs. In short, it denotes a technique for composing members into small work groups, which is based on acquired skills rather than other criteria.

[3] This fundamental translation principle formally introduced by K. Reiß and H.J. Vermeer can be summarized by “translating the meaning, not the words”. A more in-depth discussion of the principle follows in a later section.

[4] An in-depth description can be found in Odendahl’s (2015) discussion of the project.

Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.

Copyright (c) 2016 Wolfgang Odendahl

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2016. All Rights Reserved | Interface | ISSN: 2519-1268