Issue 20 (Spring 2023), pp. 157-195

DOI: 10.6667/interface.20.2023.199

Panel Paper: Innovation with and against the Tradition. Examples from Chinese, Japanese and Korean Confucianism

| Marion Eggert | Gregor Paul | Heiner Roetz |

| Ruhr University Bochum | Karlsruhe Institute of Technology | Ruhr University Bochum |

Abstract

Up until the present day, Confucianism has been a major factor in the normative discourses of East Asia. At first glance, it has sided with the preservation of the old and against innovation, according to Confucius’s self-declaration that he “only transmits and creates nothing new.” This also describes the historical role that Confucianism in distinction to other philosophies has actually played over long stretches of time. Nevertheless, Confucian ethics contains structural features, figures of thought and ideas which point beyond mere traditionalism. They reflect the deep crisis of tradition against the background of which Confucianism came into existence and which has left its mark on it. They could set free a dynamic that made it possible to distance oneself from the Confucian tradition within this tradition itself and open it up to something new, if not in terms of its creation then at least in terms of its acceptance and support. This potential also intrinsically relates to the possibility of a “modern” Confucianism.

The following three short essays do not claim to give a comprehensive account of the outlined problematique. It is only intended to throw a light upon some of the corresponding thought formations that developed in ancient China and explore by a few examples the extent to which the said potential has actually been realized in later Confucian discourse in Korea and Japan, assuming that border crossing might be among the factors to unleash it.

Keywords: Tradition and Innovation; Confucianism; China; Korea; Japan

1 A Rupture in the Origin that Opens again: A Note on Confucianism and Tradition

1.1 Confucian China – a stronghold of traditionalism?

Panelist: Heiner Roetz

When it comes to exploring the relationship between tradition and innovation, China and East Asia, inasmuch as it has been under Chinese influence, seem to be a topic of considerable importance. We have societies that on the one hand have long been considered traditionalist and on the other hand stand out through rapid scientific and technical progress. This has even led to questioning older sociological theories that saw cultural traditions as obstacles to be overcome for modern development.

Modernity, which as we know it today originated in Europe, has organized its self-understanding as a monologue with itself. China has played the role of a silent counter-image, as exemplified already in the early self-reflection of modernity in Hegel’s philosophy. Hegel identifies “free subjectivity” as the “principle” of the “modern world” and excludes China from it, and thus from modernity, as the realm of unmoved “substance.” Substance stands for the unbrokenness of the given inherited forms of life and for the traditional and anti-innovative as such. This gave rise to the image of a “stataric” (Hegel), stagnant East, into which movement can only be brought from the outside, as by colonialism, if at all. Karl Marx adopted this view, and Max Weber elaborated it in his sociology of religion. In China, Weber says, filial piety obliges as the “final ethical standard” again and again to one and the same social order as the “best of the possible worlds.” The result is the “reckless canonization of the traditional” (Weber, 1989, pp. 451, 360). Weber relates this, as Hegel had already done, to an alleged absence of transcendence in China and the prevalence of a compact world immanence without space for imagination to move.

This conception is still influential, even though it has meanwhile been thoroughly shattered by the economic boom of the East Asian region which is not easily explainable by merely external influences, together with the claim emphatically put forward by China in particular to represent a type of modernity of its own distinct from the “Western” one. This “Chinese” or “Confucian” modernity is supposed to have emerged not from a break with the past, as standard modernization theories in the wake of Weber have assumed, but from the alleged continuity of “5000 years of Chinese history.” The theory of “multiple modernities” first brought forward by Shmuel N. Eisenstadt argues in a very similar way. However, this does not do justice to the actual complexity of the historical Confucian attitude to tradition.

In what follows, I will take a look at this attitude in order to highlight its inner tension between keeping faith with the old and recognizing the voice of the present. I will argue that if traditionalism is not an apt term to describe this attitude, this is not only, as Eske Møllgaard has it, because the Confucians are obsessed with “closing the gap between the present and an imagined origin” and in this sense are “militant proponents of radical socio-ethical change” (Møllgard, 2018, pp. 34, 12). It is because there is a “gap” already in the imagined origin itself (ein Sprung im Ursprung) so that one can stand in the tradition and beyond it at the same time. The departure from tradition is already latent in it.

1.2 The crisis of tradition in Warring States China

One of the earliest debates about the validity of the old and the legitimacy of the new took place amidst a profound upheaval of the existing political, social and mental order in ancient China during the late Chunqiu and the Warring States periods (6th century to 221 BCE), the time that Karl Jaspers called the “axial age,” since he regarded it, due to its philosophical breakthroughs, as a possible turning point of world history. Different positions emerged, covering a broad spectrum of conflicting attitudes towards preservation and change. The breakdown of the old order was widely perceived as a crisis of tradition, whose reliability was questioned in a broad spectrum of differentiated arguments (Roetz, 2009). This led to a fundamental reorientation of human existence in an uprooted world that had lost its foundations and become problematic. The attempts to deal with the challenge constitute the diverging main directions of Chinese philosophy which emerges from this background.

With regard to our topic, we have on the one side of the spectrum the so called “Legalists” who combine their call for a radical innovation of the political institutions and the social structures with an uncompromising sharp anti-traditionalism and partisanship for the New—for the Legalists, the outdated knowledge transmitted from the past does not offer any solution to the unprecedented problems of the present time (Roetz 2018, pp. 44-56). On the other side, we have the Confucians with their endeavor to rescue the endangered tradition—“this culture” si wen 斯文 (Analects 9.5)—from its total loss, combined with the claim attributed to Confucius, “to transmit and not to innovate” (shu er bu zuo 述而不作) (Analects 7.1), that obviously was soon understood as a conservative maxim and attacked as such by the Mohists (see below). In spite of its traditionalistic appearance, however, Confucianism, like all ancient Chinese philosophies, is deeply marked by the crisis of tradition to which it owes its emergence. This is most evident in two central ideas of its ethics that break the frame of traditionalistic thinking: Mengzi’s ethics of compassion and Confucius’s Golden Rule.

1.3 Mengzi’s moral anthropology: spontaneity vs. historical learning

Mengzi 孟子 (ca. 370-290 BCE), like Confucius, sees himself in the tradition created by the early sages Yao 堯 and Shun 舜 and continued by their successors. Nevertheless, in order to provide an unshakeable foundation for the Confucians ethics, Mengzi claims that its core norms are rooted not just in history and past achievements but in human nature. Every human being, he says, has the innate knowledge of the good (liang zhi 良知) in itself prior to any consideration and learning,[1] thus prior to being introduced into a cultural tradition. Humans have moral impulses that here and now tell them the right thing to do, and education is only their stabilization and refinement. The good is given in the immediacy of the impulse, not only in what is mediated through tradition—an idea which certainly does not belong into a time-paradigm oriented to the past.[2]

In possessing this moral knowledge, an ordinary human being is no different from the “sages” (shengren 聖人), the early cultural heroes. The sages are little more than exemplary personifications of general human abilities who manage to act consistently in accord with them and keep them intact. But doesn’t this mean that the tradition started by them tells us something that we already know by ourselves? Mengzi doesn’t put it that way, but this is exactly how he is understood by his ancient critics Xunzi 荀子 (ca. 310-230 BCE) and Dong Zhongshu 董仲舒 (179-104 BCE), who conclude from his moral anthropology that political rule, education and the tradition of the sages, and that is, the imparting of truth through the institutions, become superfluous in the face of the moral impulse of nature.[3] Mengzi, with his delight for childlike spontaneity, is suspected of being a Daoist rebel in the Confucian camp.

Nevertheless, the passages from the Book of Mengzi became part of the Confucian canon and thus of the Confucian tradition where they have worked as an internal challenge. This enabled e.g. the Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming 王陽明 (1472-1529) to replace the authority of Confucius himself by the authority of the voice of the innate “good knowledge” postulated by Mengzi—if his heart tells him that Confucius is wrong, Wang says, then he will follow the heart and not the Master. Similarly, he will follow even the words of an ordinary person, if the heart tells him that they are right (Wang, 1976, I 72, Roetz, 1993, p. 172).

1.4 The Golden Rule: moral guidance without historical mediation

While Mengzi’s idea of spontaneous moral impulses provides a primarily affective basis for morality, the Golden Rule as formulated in Confucius’s Collected Sayings (Analects) represents a primarily cognitive approach. The Golden Rule (shu 恕) is identified with the “one that goes through all” (Analects 4.15) and introduced as something that “consisting of one single word can be practiced through all one’s life.” (Analects 15.24) It obviously occupies an important position in Confucius’s ethics. “One single word” —namely shu 恕—, this is something different than the many words of the Confucian texts and the detailed behavioral prescriptions handed down from the past. And indeed, the Golden Rule contains no more than a thought experiment that can be made again in the here and now—to reflect on one’s own likes and dislikes and imagine oneself in the role of the person affected by one’s actions or non-actions. It operates in the present moment in principle free from any transmitted knowledge. For likes and dislikes most probably refer to basic human needs beyond cultural specification (like food, clothing, living in peace etc.), as in the plausible interpretation of Analects 4.15 in the 2nd century BCE text Han shi wai zhuan 韓詩外傳 (3.38, Roetz, 1993, p. 141 f.). The Han shi wai zhuan, which illustrates passages from earlier literature, above all the Book of Songs, by short narratives, describes the corresponding attitude as that of the idealized early sage kings, the founders of the tradition. Once again, as in the case of Mengzi’s ethical nativism, we have the implicit contradiction between the role model function of the sages on the one hand and their redundancy on the other—the simple thought operation can not only be done by everyone, but it also delivers a direct normative guidance prior to all historical mediation.

That the contradiction which is implicit here could evolve into an explicit conflict is demonstrated by a passage of the Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋, a mid 3rd century BCE text which uses the thought operation of the Golden Rule to unhinge the entire tradition in a categorical shift from a law-maintaining to a law-making perspective. Rather than still following the outdated norms of the early kings, the text says, we should take into consideration, how these norms were made and on this methodical basis create new norms: namely, by “knowing the other (zhi ren 知人) through examining oneself (cha ji 察己).” Since “me and the other are the same” (ren yu wo tong 人與我同) one discovers a shared humanum by self-reflection which delivers the orientation mark for creating the new order (Lüshi chunqiu 15.8). The Lüshi chunqiu is a text of mixed composition that did not belong to the Confucian canon. Still, it shows the again explosive potential of elements of this canon that threaten to dissolve it in favor of something novel, in this case the thought figure of the Golden Rule prominently advocated by Confucius.

1.5 The Mohist paradox: no tradition without innovation

In the described theorems, there is a connection of loneliness and autarky, here in the discovery of the inner moral impulse and there in the reflection on oneself, that is a source of possible deviance. But at the same time, the Confucians, unlike all other famous philosophers of Chinese antiquity, understand themselves as loyal keepers of the cultural tradition. How does that go together? It is hardly conceivable unless the tradition itself already contains its opposite, a moment of innovation. That this is the case is the argument of the Mohists, one of the most influential “schools” of the time. They submit against the aforementioned maxim “to transmit and not to innovate” that what is now old must “once have been new” (chang xin 嘗新), and what one follows must have been “invented by someone” (huo zuo zhi 或作之) (Mozi 39, 181). The sages of antiquity, celebrated for their creative spirit, must necessarily themselves have been innovators rather than traditionalists. From this perspective, tradition would on the one hand represent its origin, the endeavor of the sages, but on the other hand, as a tradition, fall behind and betray it. For the Mohists, in this conflict there is a logical and historical primacy of the non-traditional—innovation—over the traditional, and a normative primacy of the “good” (shan 善) over the merely old.[4] Another criterion discussed in this context is “practicability” (ke 可), brought forward by the Legalists (Hanfeizi 18, 87), with the readiness for the total dismissal of the hitherto known, even by means or terror, should the old no longer be appropriate. Inspired by Legalist ideas, at the end of the Warring States period a novel form of a meritocratic centralized state has emerged that puts an end to political feudalism. It punishes “to deny the present in the name of the old” with the death penalty for the entire clan and burns books to erase any memory of the past (Shiji, 6, p. 255, Roetz, 2018, pp. 55-56).

The criterion of descent correlated with traditionalism is under attack everywhere in “axial age” China. At closer inspection, this is also true for the Confucians, although they are the most faithful to tradition. One can even speak of a Confucian solidarity with rather than addiction to tradition that is itself part of a non-traditional principled ethics of justice (Roetz, 2023). In any case, the lingering question of tradition has later largely determined the architecture of Confucian intellectual history—just as probably the history of all traditions has sooner or later been touched by the Mohist paradox, in particular if they have operated with narratives of founding figures that serve as models.

1.6 The creators of tradition as innovators and lonesome outsiders – a reflection of the mood of the “axial age” Confucian scholar

This paradox, according to which tradition implicitly contains innovation and thus its opposite, seems indeed to be inherent to the Confucian understanding of tradition as initiated by early creators of civilization. None of them is embedded in a functioning context that could be described as a living tradition itself, and they all stand against their time and their surrounding. Nearly all of the figures that appear in the famous foundation narrative in Mengzi 3a4[5] are in one way or the other outsiders. In Mengzi’s narration, Yao 堯 (trad. dated into the 3rd Millennium BCE), the first of the early sages in the Confucian canon, “alone was worried” (Yao du you zhi 堯獨憂之) about the chaotic situation on earth, which was under water because of great floods, and started the establishment of the first administrative order in order to make the world habitable. Shun 舜, Yao’s helper and successor, was the son of a criminal, and his family tried to murder him. Yu 禹 (trad. dated around 2000 BCE), the founder of the first dynasty Xia, whose father was executed, left his home for rescuing the world from the floods, and though he “three times passed the door he did not enter.” Houji 后稷, who tought the people methods of agriculture in the first government, was repeatedly abandoned as a child by his mother who regarded his birth as inauspicious, and he grew up amongst animals (Shiji 4, 111).

When we come to later times, we find the rebel Wen Wang 文王 (11th Century BCE), together with his son the founder of the Zhou Dynasty and again one of the main links in the Confucian tradition before Confucius, imprisoned by his overlord (Shiji 4, 116). His main helper Jiang Ziya 姜子牙had lived as a hermit by the sea (Shiji 32, 1478). And Confucius himself sighs that no one knows him except Heaven (Analects 14.37). He leaves his home country Lu for a thirteen-years journey through crises-torn China,[6] several times on the brink of death, his restlessness being a signature of the time. “Homeless dog” (sang jia zhi gou 喪家之狗) is shouted after him, which he self-ironically accepts (Shiji 47, 1921). He erects a mound over his parents’ grave, contrary to the customs of antiquity. His justification is this: “I am a man of the East, the West, the North, and the South. It won’t do that I don’t find the grave again.” (東西南北之人也. 不可以弗識也, Liji 4, 65) And sympathizing with two dropouts whom he comes across in the wilderness, he sighs, “I cannot live together with birds and beasts. But if do not become a follower of these people, whose follower, then, shall I be? If the world were in possession of the Dao, I would not have to take part in changing it.”[7]

Mengzi, again, who sees himself as the re-founder of the Confucian tradition which, as he deplores, was practically lost in his time, declares to “walk his way alone” (du xing qi dao 獨行其道), if necessary (Mengzi 3b2), ready to “end in a ditch” and “lose his head” (Mengzi 3b1, 5b7). And it comes as no surprise that Mengzi also slips into the role of a “creator” who hands down a work with an uncertain fate (Mengzi 2b14). Standing not only at the end of a line of tradition, but at its precarious beginning, the solitude of the zero moment repeats itself. No one else but him, Mengzi is convinced (Mengzi 2b13), is able to save the drowning world which, now metaphorically, is under water again—like in the time of the lonesome concerned sage Yao. In the ancient texts, there is a conspicuous emphasis on the subjectivity of the Confucian “gentleman” (junzi 君子) against the world, as in the his constant, sometimes coquettish reference to his “self” with the expectation and experience to be routinely misjudged and remain unacknowledged by others. He feels like an iris or orchid in the depth of the forest that is fragrant though nobody smells it (Xunzi 28, 345). Not to be acknowledged is even seen as a sign of being on the right path.[8] If necessary, the junzi will “confront thousands and tens of thousands” (Mengzi 2a2). All of these resistive motifs, totally at odds with what one would associate with an “embedded” way of life, become part of the Confucian tradition.

There is an obvious congruence with regard to loneliness, disembeddedness and tension with the world outside, then, between the world-situation in which the Confucians see themselves, that of their early heroes, and central ideas of their ethics, which mirror one another. A readiness for leaving the establish consensus is hidden in a presentation of tradition as the result of creative achievements by lonesome heroes who oppose their time. In this solitude in the midst of a hostile, ignorant environment the “axial age” Confucian scholar recognizes himself. And it seems that rather than really walking in the footsteps of Yao and Shun, he is reversely projecting his self-image on them. The personal mood of the scholar is turned into a narrative construction of the tradition of the sages.

1.7 Triggering the dynamics: borderline experiences

This would mean, however, that the disembedded Confucian puts himself above the tradition in which he stands and which he at the same time defends. The latent tension could erupt and lead to a conflict with the Confucian establishment which tried to keep the dialectics of the tradition under control by all means and defend the state of things, as in the case of the free thinker Li Zhi 李贄 (1527-1602): Influenced by Wang Yangming who is again influenced by Mengzi, he invokes Confucius himself against those who declare him untouchable, arguing that to follow the Master would betray the spirit of the Master himself (Li Zhi, 1965, p. 16f.; de Bary, 1970, p. 199). And like Mengzi, Li Zhi idealizes the infant who does not depend on the words of others but on what comes from its own mind (Li Zhi, 1965, p. 98f.; de Bary, 1970, p. 195).

This is also the point where Confucianism in principle is able to open up from within itself for deviance and, as the case may be, for the New. However, the structural potential of tradition to go beyond itself has still to be released—the elements of a tradition of second order lie behind the surface of the first order tradition into which Confucianism has in the course of time been turned. Typical triggers that create the distance are challenges by crises and external influences and changes of environment, but also the change of generations, in which a tradition must again and again be newly understood and adopted—generally speaking, the crossings of borders, generational, historical as well as geographical ones. It is for this reason that in the following contributions the focus will be on examples from Korea and Japan.

2 Traditional resources for integrating new knowledge in Korean Confucianism. The cases of Yi Ik (1681-1763) and Yi Chinsang (1818-1886)

Panelist: Marion Eggert

2.1 The limits of traditionalism among Korean Neo-Confucian literati

Korea used to be known as the country in East Asia which held most steadfastly to the Confucian tradition. This image of Korea has itself a long tradition: since at least Koryŏ times, Korea was both exonymically and endonymically known as the “land of decorum and propriety,” which first and foremost referred to its adherence to Confucian ritual and ethical norms; and it has been reinforced by the 500 years long Chosŏn dynasty’s adoption of Neo-Confucianism as state ideology. After the Chinese Ming dynasty fell to the Manchu onslaught in 1644, the Chosŏn political and cultural elite regarded itself as the last standard-bearer of Confucian civilization, and although this idea was critically reflected by some literati of the 18th century, it remained a strong ideological current until the mid-19th century, prodding the Korean educated elite to prove their adherence to Confucian doctrine. All this has contributed to the image of Korea as the place with the most conservative Confucian tradition. And yet, Korean Confucianism has never been as uninventively orthodox as this image purports. Rather, the fact that for Koreans this was a consciously and studiously appropriated tradition produced a desire to go to its roots, to understand it thoroughly as worthy successors to the great creators and innovators of this tradition, and thus prompted the unique, sophisticated debates through which Korean scholars from the 16th century onwards unfolded the finer implications of Neo-Confucian ethics and cosmology. In other words, for Korean Neo-Confucians, innovation of tradition was a hallmark of honoring tradition.

That teaching is to be received not blindly but with critical reflection is already taught in the Confucian Analects: “Learning without thinking is labor lost.” (學而不思則罔, Analects 2.15). We find the same thought expressed in the works of Ch’oe Ch’iwŏn (崔致遠, 857-after 908)—the earliest Korean Confucian scholar whose Collected Works have been transmitted until today –, although voiced in a Buddhist context: “The master’s teachings and one’s own insights enhance each other.” (故師所敎, 己所悟, 互有所長, “Muyŏm hwasang pimyŏng,” Kounjip 孤雲集kw. 2) Creating new interpretations was not frowned upon, as the cliché would have it, but recognized as achievement. The great 16th century Confucian philosopher and politician Yulgok Yi I (栗谷李珥, 1536-1584) prided himself on having “discovered what the holy men of old had not discovered” 發前聖之未發 and declared that he “knew about the folly of keeping watch of the tree-stump” (知守株之自困). (Yulgok sŏnsaeng chŏnjip 栗谷先生全集 1, “Hoek ijŏn yu yŏk pu.”) This was not just a phenomenon of the 16th century when T’oegye Yi Hwang (退溪 李滉 1501-1570) and Yi I established themselves as philosophical masters with, arguably, their own respective orthodoxy; nor is it typical only for Yi I who is regarded as the less conservative, less tradition-oriented of the two masters. Two centuries later, to give a rather fortuitous example, Yi Sangjŏng (李象靖 1711-1781) who belonged to Yi Hwang’s intellectual lineage, in a letter to Yi Suhang (李守恒, n.d.), praises the latter for his “Illustration of the Great Ultimate” (“T’aegŭksŏl” 太極說) with the following words:

Your final explanation, it washes away old opinions and makes something new out of the diagram, yet without a self-centered perspective that complicates or simplifies meaning. This is something that the men of old found difficult, but you have achieved it.

而至其後說,則濯去舊見而新是圖,少無纏繞惹絆之私,此古人之所難者而執事有焉。

Taesanjip 大山集7, “Tap Yi Chunggu” 答李仲久 [i.e. Yi Suhang])

The phrase “keeping watch of the tree-stump” (suju 守株) which appeared in the quote from Yi I above is telling in this context. It derives from the famous story by Han Fei 韓非 (ca. 280-233 BCE), a sharp critic of Confucianism, about a farmer who witnesses a hare bumping himself to death on the stump of a tree and, overjoyed about the easy meal, discards farming and instead spends his time observing the tree (Hanfeizi 49, 339). In the original text, this story is tied to the question of tradition and innovation to such a degree that the phrase suju could be translated as “stupidly observing tradition,” i.e. without reflecting the special conditions of the past that prompted the creation of that tradition. Suju became a word used for self-deprecation in the sense of “stupid,” but it never lost the original implication of “being too stupid to change one’s mind and adapt to new circumstances.” The intimate connection of suju to a lack of readiness for innovation is easily proven by a text from the mid-19th century, an encyclopedia entry which is concerned not so much with tradition but with economic and political custom; it discusses the advantages of gold and silver mining. Given, however, that reform of custom and innovation of tradition can hardly be clearly demarcated, the text may still illustrate how suju is part of the vocabulary of innovation versus conservatism:

To shy away from “changing and overcoming the dead end” just because of concerns about (people) giving up farming or causing troubles would be equivalent to “observing the tree-stump as if paralyzed.” To “restring the bow/ make reforms and start over again” as the times demand […] will sufficiently enrich households and country.

但以廢農召亂爲慮。不爲變通。則是亦守株坐困。有時更張。[…] 則寶藏興焉。家國富足矣。

(Yi Kyugyŏng 李圭景 (1788-?), Oju yŏnmun changjŏn sango 五洲衍文長箋散稿 152,

“Kŭm ŭn tong kwang pyŏnjŭngsŏl” 金銀銅鑛辨證說)

The term suju thus bears witness to the existence of a mind-set among Neo-Confucian literati that prized flexibility of thought and clearly recognized innovation not as enemy of tradition but as means for its renewal and enrichment. The fact that literati freely quoted from a text known for its decided anti-traditionalism[9] reinforces this point.

How did this play out, however, in the context of contact with an alien tradition, given that an emphatic concept of tradition is the result of challenges to tradition, be they endogenous or exogenous? For Korean Neo-Confucianism, the first decisive exogenous challenge was the advent of Western Learning—the cover term for both Christianity and Western knowledge transmitted by Jesuit missionaries to Beijing and then further transmitted by members of Korean China embassies from the turn of the 17th century onwards. (Prior to that, dealing with the Buddhist alternative had been part of the process of appropriating Neo-Confucianism as new guiding worldview, not a challenge to the latter as tradition). In 17th century Korea, news about another sophisticated civilization beyond India had the potential to de-center Chinese civilization, an intellectual situation not well compatible with Confucian convictions. This was acerbated by the Manchu victory over China. At the same time, Christianity as religion began to enter Korea, most likely as a bottom-up movement, reaching the literati class by the end of the 18th century. Although routinely persecuted, the religion slowly continued to spread throughout the 19th century; that it was perceived as a threat to Confucian predominance can be seen by the rising number of anti-Christian pamphlets authored during the first half of the 19th century.

It would be an exaggeration to say that Korean scholars had to react to this challenge; ignoring it was an option for many. However, all intellectually leading literati of 18th-19th ct. Chosŏn felt compelled to integrate this challenge into their vision of the Confucian tradition. In this brief paper, I will juxtapose two figures who represent the near-ends of the spectrum of possible reactions, Yi Ik (李瀷 1681-1763) who embraced parts of the new Western knowledge, and Yi Chinsang (李震相1818-1886) who is known as a staunch defender of tradition. And yet, I will argue, it is not so easy to mark them as “innovator” and “traditionalist” respectively.

2.2 The case of Yi Ik

Yi Ik is a very well-known figure in Korean intellectual history; he counts among the handful of persons who would be named first when talking about the so-called “empiricists” of the Late Chosŏn era—an epithet given to those whose horizon of learning went beyond Neo-Confucian moral philosophy, especially to those who openly engaged with Western Learning. Yi Ik was indeed instrumental in making Western knowledge better known to his contemporaries; his father had brought immense numbers of books from his multiple journeys as an envoy to Beijing, among them the important anthology of Jesuit works, Tianxue chuhan 天學初函. Yi Ik had read it with great interest, and since due to the breadth of his learning (and probably his charisma) he had a large number of students, he helped to propel the content of these writings into the scholarly discourse of the times. From his school emanated a generation later the first self-professed Korean Christians. Some of Jesuit natural history knowledge was incorporated into the large encyclopedic work Yi Ik authored, and his miscellaneous writings contain numerous essays on political and social reform.

Yet, Yi Ik was by no way an anti-traditionalist. Part of his rich written output were collections of the sayings of Zhu Xi and Yi Hwang to whose intellectual lineage he belonged; his disciple Chŏng Yagyong 丁若鏞 (1762-1836) spoke of him as a firm believer in Zhu Xi.[10] The topic he dealt with most frequently was Confucian ritual, usually regarded as the playground of the orthodox. He expressed much pride in Korea as the place where the ways of the ancient Chinese Zhou dynasty had been preserved, and he had the habit of calling fellow literati samun (chin. siwen 斯文), an appellation for scholars without official rank[11] which can also be used for “Confucian tradition” (“This Culture of Ours” in the phrasing of Peter Bol). After his death, he was praised and lamented by his disciples as the keeper of the Way:

While the worldly situation has deteriorated, the Way been concealed, and fake virtues create all kinds of disorder,[12] thanks to the Master the true lineage of Our Culture has not been broken. That heaven has brought the disaster of death upon him means great trouble for Our Way.

雖世衰道微。紫莠交亂。而斯文正脈。賴先生而不墜。則先生之有功於世敎。亦甚大矣。上天降禍。吾道不幸

(Yi Pyŏnghyu, “Chemun 祭文“, Sŏngho chŏnjip, purok kw. 2)

My argument is that these two sides of Yi Ik are not at all contradictory; rather, they belong together because of the way he conceived of his, the Confucian, tradition. As evidence, I provide here the preface to a collection of critical notes on Zhu Xi’s commentary on the Analects, a work he produced probably in the 1720s. The beginning of the preface provides a narrative of the core of Confucian tradition:

Humans are the most ingenious among all beings; the greatest among human beings are the sages; sagehood was most developed in Our Master (Confucius); and his teaching is best provided in the Analects. Ah! How could the world do without this book? The people of Zhou discarded it, yet it was transmitted by Confucius’ disciples; the people of Qin burnt it, but it reappeared from its place of concealment in a wall. It was overgrown by widely diverging interpretations, but Zhu Xi has found their middle ground, fixed our tradition, and gone forward against all opposition with his commentary. Ah! How could the world do without this interpretation? It is most fortunate to have it. Whoever wants to read the Analects should first read this commentary; whoever wants to read the commentary should first grasp Zhu Xi’s mind. From Zhu Xi’s mind one can more or less infer the mind of Confucius. What do I mean by “mind” [or: “core”]? When Zhu Xi made this commentary, he chose among the earlier interpretations whatever was plausible; he did not needlessly innovate. When anything was contradictory, he changed it; he did not needlessly preserve. Even his disciples, however young, could point out any difficulties they saw. Whatever little thing of value they had to say, he would take it up and not needlessly discard anything. From this we can see the heart of Zhu Xi, who […] followed only what was right [and not any social considerations]. […] His followers enjoyed his openness and voiced all their doubts, not restricting themselves out of embarrassment. This is how a gentleman should teach. Yet today, people venerate his book but do not grasp his heart, recite his text but neglect its meaning.

物莫靈於人。人莫大於聖。聖莫盛於吾夫子。而敎莫備於論語。噫。天地間何可以無此書。周人擯之。而諸子傳之。秦人火之。而壁簡復出。異說紛糾。而折衷於朱子。斯文定于一而集註於是乎孤行。噫。世敎何可以無此解。此幸之幸也。欲看此書。須先究此註。欲究此註。須先得其心。得朱子之心。夫子之心。又庶幾可推也。何謂心。朱子之爲此註。其於舊說。苟可以因則因之。不苟新也。或前後異見則易之。不苟留也。雖門人小子。隨意發難。一曲之長。咸在採收。不苟棄也。用此知朱子之心。與天地同恢。與古今同公。無一毫繫吝。而惟義之從也。然則當時取舍氣像可見。雖愚下之言。必將導以諦聽。祈或有中。使有乖妄。亦且詔而不怒。所以集長就中而爲朱子也集註也。其門人小子又樂其開納。盡情質疑。不以淺劣而自沮。是則大君子門法有然者也。其在于今。尊其書而失其心。誦其文而後其義。

(“Nonŏ chilsŏ sŏ,” Sŏngho chŏnjip kw. 49)

This account both fixes Confucian tradition and lets it loose. Tradition as narrated here is not arbitrary, it has a core of value which has been transmitted against all odds, obliterated and rediscovered. This tradition is not convention but the teaching of a truth that has to be defended against convention; and at its core, at the heart of this truthful teaching is the striving for truth in a joint endeavor. In Yi Ik’s eyes, the Confucian tradition so worthy of veneration but all too often forgotten is the weighing of arguments and critical thought itself.

This very attitude informed the way in which Yi Ik related to Western Learning. The religious part of it did not interest him much, since it asked for belief without evidence. However, he was deeply impressed by some of the more scientific ideas and arguments he found in Jesuit books. His take on Western Learning is best illustrated through a narration by one who was not at all satisfied with it, his disciple Sin Hudam 愼後聃 (1702-1761). Sin Hudam visited Yi Ik four times in the years 1724 and 1725 to discuss Western Learning with him and recorded it in a kind of diary which he titled Kimun p’yŏn 記問編, “Compilation of records of what I heard.” According to this record, this is how the extended conversation between the two scholars began:

Master Yi was just discussing with others the matter of Li Xitai 李西泰.[13] I asked: “What kind of man is Li Xitai?” He answered: “The learning of this man should not be disregarded. Seeing from his writings like The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven (Tianzhu shiyi 天主實義), the correct doctrine of the Heavenly Lord (tianxue zhengzong 天學正宗), even if his way does not necessarily fall in line with our Confucianism—when you look at where his way leads him, he can also be called a holy man.” I asked what the main doctrine of his learning was. Master Yi answered: “He says that the head is the root of receiving life, that the brain in the head is the master of the contents of memory. He also says that plants have nutritive souls (saenghon 生魂), animals have perceptive souls (kakhon 覺魂) and humans have intelligent souls (yŏnghon 靈魂).[14] These are the essential points of his learning. Although this is not identical with our Confucian teachings about the mind and human nature, how do we know he is not right?”

李丈方與人論李西太事。余問曰西太果何如人。星湖曰此人之學不可歇者。今以其所著文字如天主實義天學正宗等諸書觀之。雖未知其道之必合於吾儒。而就其道而論其所至則亦可謂聖人矣。余問曰其學以何爲宗。李丈曰其言云頭者受生之本也。頭有腦囊爲記含之主。又云草木有生魂禽獸有覺魂人有靈魂。此其論學之大要也。此雖與吾儒心性之說不同而亦安知其必不然也。

(“Kimun p’yŏn,” first entry. In: Sin Hudam 2006, vol. 7)

To the great dismay of Sin Hudam who had only recently abjured his previous fascination with heterodox readings and wished to be guided on the Confucian Way, Yi Ik showed himself ready to discard tradition as truth criterion. Although this attitude paved the way for some of his disciples to reject all claims of the tradition to their allegiance, for Yi Ik himself, this openness stood in no opposition to the Confucian Way but carried on the best part of it.

2.3 The case of Yi Chinsang

Just like Yi Ik, Yi Chinsang was hailed as a guardian for the Confucian Way in lifetime and after his death; different from Yi Ik, this is the way he is remembered until today (and the reason why he is far less remembered in spite of his intellectual stature as one of the leading scholars of the mid-nineteenth century).[15] An obituary poem by (today forgotten) Ch’oe Kyŏngmok 崔慶穆 (n.d.) puts the general image his contemporaries held of Yi Chinsang in a nutshell:

He shouldered the burden of safeguarding our tradition (samun) and devoted all his energies to upholding the general good and overcoming himself. Now that his star has sunk behind the horizon, our Way will be in obliteration. 擔護斯文責。惟公克有功。德星沈左海。吾道竟夢夢.

(Hanju chip, purok kw. 4)

For Yi and his contemporaries, living in a time when the missionaries brought their books on cannon boats, the Western challenge was not a purely ideological one anymore. Yet what bothered Yi Chinsang most was the fear that the “foreign teaching” (igyo 異敎) could take over and push Confucianism aside; in his writings, he time and again lamented this prospect. His answer to the threat was an emphatic concept of tradition (samun, odo 吾道) as well as an intellectual bolstering up of this tradition. In order to safeguard the Confucian tradition, Yi Chinsang felt he had to re-interpret it for his day; he did so creatively and by adapting some structural elements of the tradition that he wanted to refute.

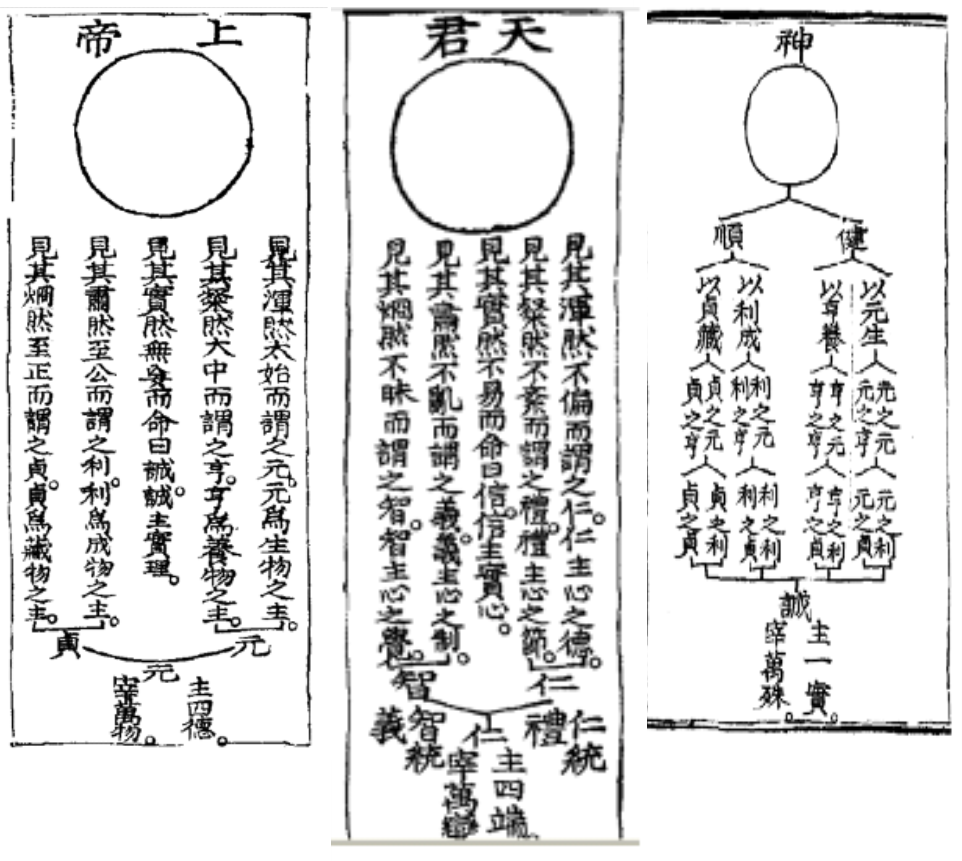

Space allows me to provide here only one example, a treatise with diagrams on chujae 主宰 (“Chujae tosŏl” 主宰圖說, Yi Chinsang, Hanju chip 寒州集, kw. 34), the “controlling power” which is traditionally (i.e., already in Zhuzi yulei 朱子語類) identified with both the “principle” (li 理) and the human mind (xin 心). As can be seen in Figure 1, in illustrating these identifications in the diagrams to which his treatise is attached, Yi Chinsang takes recourse to something that looks like the Holy Trinity: Sangje 上帝, the Supreme Ruler, in his words: “the controlling power of Heaven and a reverent name for the Heavenly principle;” Sin 神, the Spirit, “the spread of the Mandate of Heaven and the miraculous working of the principle“, which is the source of the expression of li in the material world; and finally ch'ŏn'gun 天君 or “the heavenly Lord,” a comparatively rarely used word for the human mind derived from the Xunzi 荀子 (Xunzi 17, 206 f.) which is, in Yi's explanation, “the reverent name for the human principle”.

Figure 1: Diagrams in Yi Chinsang, 李震相 “Chujae tosŏl” 主宰圖說

All three words, sangje 上帝, sin 神, and ch'ŏn'gun 天君, are reminiscent of the Christian God: the first two terms had both been adopted by Protestant missionaries as appellation for God, while the latter might be translated into Korean as hananim (“Lord of Heaven”), just like the Catholic word for God, ch'ŏnju 天主. All three are also emanations, or different aspects, of Heaven: Sangje refers to the unity, sin to the all-pervasiveness, ch'ŏn'gun to the human embodiment of Heaven. Again, this sounds not unlike a monotheistic theology of an almighty, omnipresent god who resides in everbody’s heart. And finally, this “Heaven” seems identical with, or at least unseparable from, li 理. While stopping short of a personification of the “principle,” Yi Chinsang’s metaphysics are quite obviously meant to recapture Heaven, tian, for Confucianism. With the rendering absolute of a transcendent power on the one hand, and the strengthening of human agency through the identification of the human mind with li on the other hand, his teaching already contains all the elements necessary for the ultimate “religiosification” of Confucianism for which his son Yi Sŭnghŭi became an important proponent.

Thus, with thinkers like Yi Chinsang a religious fervor entered Neo-Confucianism that had not been extant in the 17th and 18th centuries. Scholars of this era now emphasized the metaphysical aspects of their tradition over the ethical ones to a degree which is in some ways—as I could hopefully illustrate—curiously reminiscent of the Christianity they fought against. The struggle to hold up the tide of Catholicism had resulted in structural accommodations of the “foreign” into the “own” in a way that helped to prepare the ground for Confucianism to recognize itself as one of the “religions” when this neologism was brought to Korea. The Neo-Confucian refutation of Christianity, be it polemical, discursive or implicit, ended up locking both into an antonymic relationship within the emerging religious field from which Neo-Confucianism never managed to disentangle itself. In other words, by struggling to refute Catholicism, Neo-Confucian scholars construed an “other” that became more constitutive for their “self” than they may have imagined, but this move helped to secure a place for their “teaching” in the world of “religion.” Doubtlessly, then, Yi Chinsang’s attempt to safeguard tradition did work and could work only through innovation.

2.4 Concluding remark

Innovation was concealed behind both scholars’ rhetoric of tradition, in a way analogous to how in the period of transition to modernity around 1900, traditional thought was concealed behind the modernizers’ rhetoric of innovation.[16] Admittedly, there is nevertheless a marked distinction between the two scholars treated here concerning their attitudes towards tradition, in that they are of different opinion about the reach of tradition’s authority. And yet, taken together the two vividly illustrate the innovative power of the Korean Confucian tradition.

3. Catalysts of Innovation and Modernization in Japanese ‘Confucianism’

Panelist: Gregor Paul

3.1 Introduction

In the 19th century many Japanese intellectuals who criticized the Tokugawa Shōgunate (1600-1868) as a reactionary and outdated system regarded the Shōgunateʼs reliance on Shushigaku 朱子学, the Japanese ‘Neo-Confucian’ “School of Zhu Xi [1130-1200],” as one of the main reasons for these evils. In their demands for a thorough reform, if not radical change, they utilized philosophies developed within other branches of Japanese ‘Confucianism,’ especially the Kogaku(ha) 古学(派), i.e., the “School of Ancient [Confucian] Learning,” and the Shingaku(ha) 心学(派), i.e. Wang Yangming’s 王陽明 (1472-1529) “School of Heart-and-Mind.” Main representatives of these schools were Itō Jinsai 伊藤 仁斎 (1627-1705), and Kumazawa Banzan 熊沢蕃山 (1619-1691), respectively. The two schools emphasized Mengzi’s 孟子 (ca. 370-290 BCE) justification (if not obligation) of forcibly doing away with an inhumane government, and the right to individual decision based on an individual’s unfailing innate knowledge. When, in 1837, Ōshio Heihachirō 大塩 平八郎 (1793-1837) started a rebellion against the inhumanity of the Shōgunate, he was inspired by the teachings of Mengzi and Wang Yangming. During the early years after the Meiji Restauration (1868), the Mengzi was referred to as a means of the ‘Confucian’ tradition itself (i.e. original ‘Confucianism’ itself) that could overcome Neo-Confucian based Tokugawa reactionism and thus pave the way for a humane and modern sociopolitical system.

3.2 Classic Confucianism versus Neo-Confucianism

In my contribution, I offer examples of traditions or ways of thought that determined Japanese politics between 1868 and 1945. While some of these traditions opposed egalitarian, democratic, and universal rights ideas, others favored such ideas, and used them to argue for respective political innovations. Both ways of thought were conceived of as ‘Confucian’ traditions, though the label ‘Confucian’ is not unproblematic.[17]

Independent of this problem, one should be aware that the term “tradition(s)” can refer to more or less broader orientations, schools, or lines of history. The wider a notion of a tradition, the more probably it includes both, conservative and innovative strains or tendencies. For instance, Chinese history as a whole includes such different traditions as ‘Confucianism’ and radically anti-traditional Legalism. But even within ‘Confucianism,’ we find both, traditionalism and innovationalism. Actually, the name ‘Confucianism’ refers to a considerable number of different teachings and practices which can aptly be distinguished by such labels as ‘fundamentalist’, ‘reactionary,’ ‘closed,’ ‘conservative,’ ‘critical,’ ‘tolerant,’ ‘open,’ ‘progressive,’ and ‘revolutionary.’ Moreover, even if it comes to ‘Confucian’ individuals—as for example the Korean studies scholar Marion Eggert deals with in her contribution to this volume—we are often forced to admit that their teachings cannot be reduced to mere conservatism or anti-conservatism. The Japanese scholar and writer Ueda Akinari 上田秋成 (1734-1809) who is regarded as an adherent to the nationalist (or nativist) school of Kokugaku 国学, the “School of our homeland [Japan],” also criticized the school’s normative notion of cultural identity, emphatically put forward by the Kokugaku scholar Motoori Norinaga 本居 宣長 (1730-1801). Usually both, conservative and innovational orientations, become especially apparent and are strengthened if they get acquainted, or confronted, with ‘external’ or ‘foreign’ traditions—as it was the case with the opposition between ‘Confucianism’ and Legalism and the confrontation of Japanese culture with ‘the West.’ Such contacts lead to defending (what is regarded as) one’s own (especially one’s indigenous) ‘beliefs’ and customs, or to advocating changes, respectively.

In what follows, I focus on what I regard as the main branches of Chinese and Japanese conservative and progressive ‘Confucianism’. The most important conservative ‘Confucian’ branch, the so-called ‘Neo-Confucian’ Shushigaku, the “School of Zhu Xi (1130-1200),” had originated in 12th century China. The most important progressive line was dubbed Kogaku-ha, “School of Ancient Learning.” This name referred to classic ‘Confucianism,’ as put forward in the Lunyu (Analects, Jap. Rongo, mainly attributed to Confucius, 551-479 BCE), the (Book of) Mencius (Jap. Mōshi, attributed to Mengzi), and the (Book of) Xunzi (Jap. Junshi, mainly attributed to Xunzi 荀子, ca. 310-230 BCE). Roughly speaking, the first line of thought was supportive of the Tokugawa Shogunate, a rather oppressive system ruled by the Tokugawa clan samurai, established in 1600. Its idea of a strong and untouchable rule was supported by nationalist and chauvinist traditions, namely the teachings of the Kokugaku, and Tennōism, a doctrine according to which the tennō was a ‘living god’ who (because of his divinity) must under no circumstances be dethroned, and who, like a father, ought to be ‘loved’ and obeyed by the Japanese people.[18] (Of course, during the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), the tennō did not hold real political power.) Shushigaku, Kokugaku, and Tennōism were anti-egalitarian and decidedly anti-democratic movements.

Classic ‘Confucianism’ had been introduced to Japan latest during the 6th century, and had played an almost revolutionary—and in this sense innovational—role already in the establishment of a new political system during the early 7th century. One may very well regard this as a significant indication of the innovational humane potential of classic ‘Confucianism.’[19] In 17th century, the Kogaku-ha scholar Itō Jinsai, in an astounding appraisal of the humane and anti-despotic teachings of Mengzi, strongly criticized Shushigaku and Kokugaku. In particular, Jinsai emphasized the Mencian notions of human dignity, the importance of ordinary people, and the Mencian justification of what may be called tyrannicide. Jinsai completely agreed with the Mencian notion of individual human dignity, namely the concept of tianjue (Jap. tenshaku 天爵), according to which every single human being is endowed by nature with a value that consists in, what for the sake of brevity may be characterized as, moral autonomy.[20] He even went further than Mencius when emphasizing that not only “high” (kami 上), but also “low” (shimo 下) people, i.e. ordinary people had the right to forcibly do away with despots. Jinsai also stressed the Mencian notion that the people—and not the rulers—are the foundation of a nation (Tucker, 1998, especially pp. 192, and 35-36). Similarly, Banzan argued in favor for a non-oppressive politics (McMullen, 1999). In so doing, he was also inspired by Wang Yangming whose emphasis on the Mencian teaching that every human possesses unfailing innate intuitive knowledge (Chin. liangzhi, Jap. ryōshin 良知) became justifications of an ever stronger ‘individualism’ than in the Book of Mencius. The uprising by Heihachirō I mentioned in my introduction was inspired by ideas of Wang Yangming. I need not emphasize that the ideas of individual moral autonomy and individual innate knowledge became catalysts for later anti-traditional, i.e. anti-authoritarian movements.

3.3 Developments since the Meiji Restauration 1868

After 1868, inspired by such ‘Western’ philosophers as Rousseau (1712-1778), John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), and especially Kant (1724-1804), and impressed and at the same time repelled by ‘Western’ military power and general sociopolitical developments that they attributed, among other things, to ‘Western’ democracy, eminent Japanese scholars expressed similar and even stronger admiration for these Mencian teachings than Jinsai had voiced. Explicitly referring to Mengzi, they went as far as demanding instituting “peoples’ rights” and even “human rights.” That is to say that they indeed tried to utilize what they regarded as original Sino-Japanese traditions, that is one of their own traditions, as means for achieving radical sociopolitical changes. Their ideas can indeed be adequately called innovational since though including traditional notions, they also implied the radically new ‘Western’ ideas of democracy and human rights. This should, however, not lead to underestimating the traditional influence. This influence became a significant catalyst of their demands and was used as a counter-argument against the argument that democracy and human rights were something utterly ‘foreign’ and therefore no acceptable means to determine Japanese culture and politics. Generally speaking, reliance on—and reference to—one’s own traditions can be an efficient means to counter the argument that an idea is of (mere) foreign origin and must therefore be rejected.

However, in spite of these scholars’ sharp criticism of Shushigaku and chauvinism, and their reference to classic ‘Confucianism’ as an old-standing Japanese tradition, the chauvinist, anti-egalitarian, and anti-democratic powers dominated Japanese philosophy, ideology, and politics till the end of the Second World War. This ideology culminated in the publication of the Kokutai no hongi 国体の本義, “The original truth of our national essence,” a pamphlet that, among other things, explicitly rejected the teachings of Mengzi (Kokutai no hongi 1949, p. 150; see also p. 177). They also exploited a traditional narrative, used in a story by Ueda Akinari, according to which ships from China that carried the Book of Mencius did not reach the Japanese shore (Ueda Akinari, 1977, p. 102; 1971, pp. 61-62). However, and as mentioned above, this scholar, though regarded as an adherent of the Kokugaku, criticized its chauvinist propagators, thus also actually indicating that one should be open for ‘foreign’ ideas. This becomes especially clear from his succinct statement that “Wherever a country, the spirit of the country is its stench” (Doku no kuni demo sono kuni no tamashii ga kuni no shūki nari どこの国でも其国のたましいが国の臭気也). (Ueda Akinari, Tandai shōshinroku 胆大小心録 1808, NKBT, vol. 56, 312). Again generalizing: normative notions of a unique cultural identity are strongly supportive of traditionalism and even ethically and politically questionable.[21]

In what follows, I briefly present three examples of the way Japanese scholars used the Mencius to demand a politics that honored ideas of democracy and human rights. The first one is related to the Meirokusha, the “Society of Meiji 6” and its journal Meiroku zasshi. The second and third ones are simply clear evidence that Japanese scholars who asked for democracy and human rights were indeed convinced that their demands could by supported and even justified by reference to the Book of Mencius.

The Society of Meiji 6 was founded in 1874. Because of increasing restriction of freedom of speech, it dissolved itself already one year later. The members of the society included some of the most progressive and brilliant intellectuals of the time, among them scholars who argued for human dignity, democracy, and human rights, often supporting their arguments by at least implicit reference to the Book of Mencius. Two of the most famous members, namely Nishi Amane 西周 (1829-1897) and Tsuda Mamichi 津田真道 (1829-1903), however, also explicitly argued against traditionalism by pointing out that one cannot get an ought from an is, i.e. that one cannot defend one’s culture and customs by merely arguing that they are traditions. Also, Nishi stressed—thus arguing against conservative Neo-Confucianism—that one should clearly distinguish between the way of heaven and the way of man, i.e. natural laws and social norms. Nishi Amane was influenced by the Kogaku-ha scholar Ogyū Sorai 荻生 徂徠 (1666-1728) who in turn was strongly influenced by Xunzi (Paul in Ommerborn, Paul & Roetz, pp. 762-767). Tsuda attacked every kind of superstition.

My second example is the scholar Nakae Chōmin 中江 兆民 (1847-1901). Since he had translated parts of Rousseau’s Contract Social (in 1882), he was nicknamed “Rousseau of the East.” He maintained that the principles of freedom, equality, and justice also existed in China as especially put forward in the Book of Mencius, and were thus no exclusively Western “possessions.” Though he conceded that an emperor ought to be venerated, he also pointed out that veneration should depend on whether the emperor himself honored the named “principles” (Paul in Ommerborn, Paul & Roetz, 2011, pp. 802-804). Note that Chōmin, by basing his views on both, ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ traditions, argued for a universally valid ethics, thus providing an exemplary instance of the influence ‘foreign’ ideas can have on realizing that there traditionally exist similar ideas in one’s own culture that, moreover, could and ought to be used as incentives for similar innovations as were already carried through in other cultures.

The third example is Kōtoku Shūsui 幸徳 秋水 (1871-1911). Because of what the government regarded as intolerably revolutionary ideas, Kōtoku was executed in 1911. In 1903, he said that he, like Chōmin, based his fundamental convictions on the Book of Mencius. In 1906, he further stated that he had always been a fond reader of radical, anti-nationalist, anti-militarist, and anarchist books, and that his [respective] readings included the Book of Mencius and the Daodejing (Paul in Ommerborn, Paul & Roetz, 2011, p. 804).

3.4 Illustrations of Japanese Nationalism and ‘Universalism’

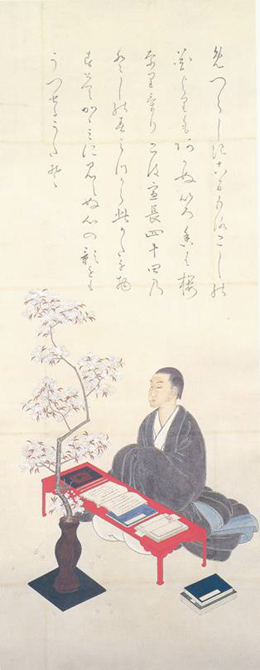

I conclude my paper by showing pictures exemplarily illustrating the tradition of Kokugaku and Kogaku-ha. The first one (Figure 2) is a self-portrait of the most influential representative of the Kokugaku, Motoori Norinaga.[22] He shows himself together with cherry blossoms, about which he wrote the famous poem:

Shikishima no 敷島の

Yamato gokoro wo 大和心を

Hito towaba 人問わば

asahi ni niou 朝日に匂ふ

yama-sakura-bana 山桜花

If you ask for the heart of Yamato [Japan] –

The blossom of the mountain cherry

In the fragrance of the morning sun.

Figure 2: Motoori Norinaga, self-portrait

The critical kokugakusha Ueda Akinari whom I referred to above, countered Norinaga’s poem by the following poem of his own:

Shikishima no しき島の

yamato gokoro no やまと心の

nan no ka no なんのかんの

uronna koto wo うろんな事を

mata sakura bana 又さくら花

Again this mumbo jumbo

About the heart of Yamato

And its cherry blossoms.

(Tandai shōshinroku 胆大小心録1808, NKBT, vol. 56, 312)

About Mengzi Norinaga remarked, in the vein of the Legalist critique that Confucianism supported rebellion (Hanfeizi 51):

Mencius, whom the Confucianists revere as a sage in the same class with Confucius, was quite different [from Confucius]. […] He encouraged revolt (doing away with one’s souvereign which under no circumstances is admissible) wherever he went. He was no less evil a person than Tang 湯 and Wu 武 (the founders of the Dynasties Shang and Zhou, idealized as legitimate rebels by the Confucians).

(Motoori Norinaga, Kuzubana, MNZ V, 466, trans. Tsunoda et al., 1958, p. 529)

The second picture (Figure 3) shows a sculpture of Mengzi that in 2005 China presented to the Japanese university Ritsumeikan. Ritsumei (Chin. liming 立命) is a term from the Menzius (7a1) which, roughly put, implies that one ought to follow the rules of humaneness (Chin. ren 仁, Jap. jin).[23] The present did of course not express an agreement with Mengzi’s philosophy of government, but simply the Chinese government’s intention to improve Chinese-Japanese relations.

Figure 3: A statue of Mengzi

4 Final remark

Though brief, my discussion of tradition and innovation in the history of ‘Confucianism’ in Japan from 17th to 20th century may suffice to refute the prejudice that traditional Sino-Asian cultures as such did not develop ideas of human dignity and, being averse to innovation, did not use them as a means to argue for sociopolitical modernity and human rights as the epitome of the new—though this happened rather late, as it was the case in Western cultures, too.

References

Analects 論語 (1972). Harvard-Yenching Sinological Index Series, A Concordance to the Analects of Confucius 論語引得. Reprint Taipei: Chengwen.

Ch’oe Ch’iwŏn 崔致遠. Kounjip 孤雲集. https//db.itkc.or.kr.

Chŏng Yagyong 丁若鏞. Yŏyudang chŏnjip 與猶堂全集. https//db.itkc.or.kr.

De Bary, Wm Th. (1970). Individualism and Humanitarianism in Late Ming Thought. In de Bary (ed.), Self and Society in Ming Thought. New York: Columbia UP, 145-248.

Hanfeizi 韓非子 (1978). Han Feizi jijie 韓非子集, Zhuzi jicheng 諸子集成, vol. 5. Hong Kong: Zhonghua shuju.

Hanshi Waizhuan 韓詩外傳 (1972). Lai Yanyuan 賴炎元, Hanshi waizhuan jinzhu jinyi 韓詩外傳今註今譯. Taipei: Shangwu yinshuguan.

Jullien, F. (2021). There is No Such Thing as Cultural Identity. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons.

Katō Shuichi (1981-1990). A History of Japanese Literature. 3 vols. Tokyo, New York & San Francisco: Kodansha International.

Kokutai no hongi: Cardinal Principles of the National Entity of Japan (1949). Trans. John Owen Gauntlett, ed. Robert King Hall. Harvard University Press.

Li Zhi 李贄 (1975). Fenshu, Xu Fenshu 焚書, 續焚書. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.

Liji 禮記 (1977). Wang Meng’ou 王夢鷗, Liji jinzhu jinyi 禮記今註今譯. Taibei: Shangwu yinshuguan.

Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋 (1978). Zhuzi jicheng 諸子集成, vol. 6. Hong Kong: Zhonghua shuju.

McMullen, J. (1999). Idealism, Protest and The Tale of Genji: The Confucianism of Kumazawa Banzan (1619-91). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mengzi 孟子 (1973). Harvard-Yenching Sinological Index Series, A Concordance to Meng Tzu 孟子引得. Reprint Taipei: Chengwen.

Møllgaard, E. (2018). The Confucian Political Imagination. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Motoori Norinaga 本居宣長 (1926-1927). Motoori Norinaga zenshū 本居宣長全集 (MNZ), 10 vols., ed. by Motoori Seizō, Tokyo.

Mozi 墨子 (1978). Mozi jiangu 墨子閒詁 Zhuzi jicheng 諸子集成, vol. 4. Hong Kong: Zhonghua shuju.

NKBT 日本古典文学大系. Great Collection of Old Japanese Literature. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten 岩波書店 1958-1966.

Noh, Kwan Bum (2016). “Academic Trends within Nineteenth-Century Korean Neo-Confucianism.” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 28, 159-191.

Ommerborn, W., Paul, G. & Roetz, H. (2011). Das Buch Mengzi im Kontext der Menschenrechtsfrage, Berlin: LIT.

Paul, G. (1993). Philosophie in Japan, München: Iudicium.

———. „Kulturelle Identität: ein gefährliches Phänomen?“ Interkulturelle Philosophie und Phänomenologie in Japan, ed. M. Lazarin, T. Ogawa & G. Rappe, München: Iudicium: 113-138.

———. (2001). Philosophy of human rights, Japanese, Routledge Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy, ed. Oliver Leaman, London, New York: Routledge, 425-429. Includes also other texts that deal with the topic of my article.

———. (2006). Motoori Norinagas (1730-1801) Selbstporträts und die Menzius-Skulptur der Ritsumeikan-Universität: Japanische Menzius-Kritik und Menzius-Verehrung im Spiegel Bildender Kunst, Mitteilungsblatt [der Deutschen China-Gesellschaft] [Bulletin of the German China Association] 1/2006: 47-62. Bochum: Bochumer Universitätsverlag.

———. (2010). Notions of cultural identity—a dangerous myth? European Journal of Sinology 1/2010: 52-74.

———. (2018). Literatur und Philosophie in Japan. Bochum: Projekt-Verlag.

———. (2022). Philosophy in the History of China. Bochum: Projekt-Verlag.

Roetz, H. (1993). Confucian Ethics of the Axial Age. A Reconstruction under the Aspect of the Breakthrough toward Postconventional Thinking. Albany: SUNY Press.

———. (2009). Tradition, Universality and the Time Paradigm of Zhou Philosophy. Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 36 (3), 359-375.

———. (2018). Zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft. Der Aufstieg der Gegenwart im China der Zeit der Streitenden Reiche (Between the Past and the Future. The rise of the Present in Warring States China). Bochumer Jahrbuch zur Ostasienforschung 41, 17-67.

———. Just Roles and Virtues? On the Double Structure of Confucian Ethics, forthcoming in Journal of Chinese Philosophy.

Schleichert, H. & Roetz, H. (2021). Klassische chinesische Philosophie. Frankfurt/M.: Klostermann.

Schmid, A. (2002). Korea Between Empires, 1895-1919. New York: Columbia University Press.

Seoh, Munsang (1977). “The Ultimate Concerns of Yi Korean Confucians: An Analysis of the i-ki Debate.” Occasional Papers on Korea 5, 20-66.

Shababo, G. (2011). “The Structure of the Doctrine of the Mean in Diagrams.” M.A. Thesis, University of British Columbia.

Shiji 史記 (1969). Hong Kong: Zhonghua Shuju.

Sin Hudam 愼後聃 (2006). Habin sŏnsaeng chŏnjip 河濱先生全集, 9 vols.. Seoul: Asea munhwasa.

Toynbee, A. (1951). A Study of History. 5th ed.. London, New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Tsunoda, R., et al., eds (1964). Sources of Japanese Tradition. New York, London: Columbia University Press.

Tucker, J. A. (1998). Itō Jinsaiʼs Gomō jigi and the Philosophical Definition of Early Modern Japan. Leiden: Brill.

Ueda Akinari (1971). Tales of Moonlight and Rain: Japanese Gothic Tales by Ueda Akinari. Translated by Kengi Hamada. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

———. (1977). Ugetsu Monogatari: Tales of Moolight and Rain. Translated by Leon Zolbrod. Tokyo: Tuttle.

Wang Yangming 王陽明 (1976). Wang Yangming quanji 王陽明全集. Taipei: Zhengzhong.

Weber, M. (1989). Die Wirtschaftsethik der Weltreligionen. Konfuzianismus und Taoismus. Schriften 1915-1920. Max Weber Gesamtausgabe I/19. Tübingen: Mohr.

Xunzi 荀子 (1978): Xunzi jijie 荀子集解, Zhuzi jicheng 諸子集成, vol 2. Hong Kong: Zhonghua Shuju.

Yi Chinsang 李震相. Hanju chip 寒州集. https//db.itkc.or.kr.

Yi I 李珥. Yulgok sŏnsaeng chŏnjip 栗谷先生全集. https//db.itkc.or.kr.

Yi Ik 李瀷. Sŏngho chŏnjip 星湖全集. https//db.itkc.or.kr.

Yi Kyugyŏng 李圭景. Oju yŏnmun changjŏn sango 五洲衍文長箋散稿. https//db.itkc.or.kr.

Yi Sangjŏng 李象靖. Taesanjip 大山集. https//db.itkc.or.

[1] Mengzi 7A15: “What humans are capable of without having to learn is their good capacity. What they know without having to deliberate is their good knowledge.”人之所不學而能者 其良能也. 所不慮而知者 其良知也.

[2] Cf. for this topic Roetz 2009.

[3] Cf. Roetz, 1993, p. 221 f.

[4] Mozi 46, 261 f: “One should transmit the good of antiquity and create the good of today, in order to increase the good all the more.” 吾以為古之善者則誅(述)之 今之善者則作之 欲善之益多也.

[5] “At the time of Yao, the world was not yet settled. Great floods crisscrossed and inundated the whole world. Grasses and trees grew thickly, and the animals gathered en masse. The grain could not grow, and the animals harassed the people. The paths left by the tracks of the animals crossed [even] on the territory of the [later] central states. Yao alone was worried about this. He raised up Shun and had him establish an [administrative] order. Shun let Yi handle the fire, and Yi burned the forests and swamps so that the animals fled and hid. Yu made the nine rivers flow again, cleared the beds of the Ji and the Ta and led them to the sea. He created a drain also for the waters of the Ru and the Han and opened the Huai and the Si and led them into the Jiang. Only then became it possible to live in the central states. At that time, Yu was eight years away from his home. Three times he passed the door of his house, but he did not enter. If he had wished to cultivate his fields, could he have done so? Houji learned the people sow and harvest and plant the five kinds of grain. The grain ripened, and the populace grew. But the way of humans is such that they become almost like animals if they are well fed, warmly clothed and comfortably housed and receive no education (a contradiction to Mengzi 2a6). So the sage (Shun) was worried again, and he let Xie as Minster of Education instruct the people about the human relations. […]” 當堯之時天下猶未平。洪水橫流,氾濫於天下。草木暢茂,禽獸繁殖,五穀不登,禽獸偪人。獸蹄鳥跡之道交於中國。堯獨憂之,舉舜而敷治焉。舜使益掌火,益烈山澤而焚之,禽獸逃匿。禹疏九河,瀹濟漯而注諸海,決汝漢,排淮泗而注之江。然後中國可得而食也。當是時也禹八年於外,三過其門而不入。雖欲耕,得乎? 后稷教民稼穡, 樹藝五穀。五穀熟而民人育。人之有道也,飽食煖衣逸居而無教則近於禽獸。聖人有憂之,使契為司徒教以人倫。

[6] Cf. Toynbee 1951, vol. III, pp. 248-263, on the “Withdrawal-and-Return motif.”

[7] Analects 18.6 鳥獸不可與同群。吾非斯人之徒與而誰與?天下有道,丘不與易也。

[8] Cf. for this topic Roetz 1993, pp. 162, 166-167 and 170-173.

[9] For a concise account of anti-traditionalism in the Hanfeizi see Schleichert & Roetz (2021, pp. 222-225).

[10] Chŏng Yagyong, Letter to Yi Mundal, Yŏyudang chŏnjip 與猶堂全集 munjip kw. 19, 281_408d.

[11] The term (in the meaning of “our culture”) is derived from Analects 9.5. In the present function, the word may best be understood as meaning “cultivated person.” Of course, Yi Ik was not alone in using samun in this sense, but it seems to appear more frequently in his Collected Works than in any other such collection contained in the fully searchable Han’guk munjip ch’onggan database (itkc.or.kr).

[12] Literally, “the darnel and the bluish red create confusion [with corn, and with vermilion].” Allusion to Mengzi 7b37. The preceding 世衰道微 alludes to Mengzi 3b9.

[13] This is, of course, the Chinese name of Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), author of the Tianzhu shiyi. Note that Xitai seems to be used generically for the authors of Jesuit writings—Jesuit texts like Zhifang waiji 職方外紀, a collaborative work, and Tianwenlüe 天問略, authored by Manuel Dias Jr. (1574-1659), are also subsumed under “Xitai’s” works.

[14] For translation of the terms for the soul, which are Aristotelian in origin, I have used the terms generally in use in English for Aristotle’s psychology. It should be noted that yŏnghon has quite different connotations from “rational soul” and would be far better translated as “spiritual soul.”

[15] In Western language studies of Korean intellectual history, Yi Chinsang is mostly just mentioned in passing (e.g. Noh 2016, p. 183), In both English language works treating him more extensively which I could discover, his innovations in some finer points of Neo-Confucian argumentation have been pointed out (Seoh 1977, p. 55; Shababo 2011, pp. 47f.), even while claiming that he “was not an innovator” (Shababo 2011, p. 48), Yi has of course been well studied in Korean language; however, the undercurrents of responses to Christianity in his thinking seem to have remained largely undetected so far.

[16] As one example of numerous studies showing this, see Schmid 2002, 80-86.

[17] Like the other two authors and for the sake of convenience, I follow the convention of using the label ‘Confucianism’ instead of using the respective Chinese designations. As to the problems of this label, see (Paul, 2022, pp. 22-33). To avoid any misunderstanding, in my approach I deal with what may be called traditional ‘Japanese Confucianism’ (which includes reception of classic Chinese Confucianism) and different kinds of Chinese Neo-Confucianism. This enables offering a differentiated account of the ‘innovating’ and ‘conservative’ forces inherent in Confucianism, and of their influence in Japanese intellectual history

[18] See my explanation of Tennōism in Ommerborn, Paul & Roetz (2011, pp. 824-829).

[19] For a detailed treatment of the Japanese reception of the Mengzi in early Japan, see Paul (1993) and Paul (2018, pp. 27-29).

[20] For a comprehensive discussion of the Mencian notion of individual autonomy and human dignity, see Paul (2022, pp. 119-129).

[21] I have tried to show this in detail in Paul (1998), and Paul (2010). More recently, Franҫois Jullien (2021), expressed similar views, warning against the “dangers” of the notion of cultural identity (though, in my opinion, he confuses facts and norms and history and logic, in this way perhaps even contradicting himself).

[22] For details, see Paul 2006, and Paul in Ommerborn, Paul & Roetz 2011, pp. 719-727.

[23] For details, see Paul 2006, and Paul in Ommerborn, Paul & Roetz, 2011, pp. 736-741.

accepted March 22, 2023]

Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.

Copyright (c) 2023 Heiner Roetz

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright © 2016. All Rights Reserved | Interface | ISSN: 2519-1268